- Home Page

- INL_USANews

- INLWorldNews

- AustralianAsiaNews

- Contact Us

- WikiLeaksJulianAssange

- USPlanToDestroyWikiLeaks

- US_SetUP_JulianAssange

- AFP_WikiCommitsNoCrime

- WhatIsWikiLeaks?

- AssangeFearsMurderInUSA

- Collateral MurderVideo

- Wiki_Guardian'sUSCables

- Persson_Lindh_Murder_CIA

- Anna Lindh'sMurde_rCIA

- DomocracyNow_WikiLeaks

- CIASetUpJullianAssange

- WikiLeaksCables30Dec2010

- WikiLeaks_Mirrors

- GenocidebyNaziT4Dctors

- GodHelpAmerica&TheWorld

- RothschildOwnWarCIA_MI5

- RothschildNWOMassMurders

- RothschildMI5_CIA_Mossad

- RothschildMI5SovietAgent

- Glen_Kealy_the Sculptor

- rothschildarchives

- NoArms_NoLegs_NoWorries

- HouseOfRothschildP1

- RothschildsWorldControl

- WikiLeaksTruthAlwaysWins

- WatersWrongfulConviction

- RothschildsWorldControl1

- BernardMadoffPonziScheme

- USAStarSpangledBanner

- Elle_Magazine_Highlights

- TheInnocenseProject

- FentonTwevellian_Poems

- FrontLineJournalismClub

- CorruptLondonMetPolice

- CorruptLondonAttorneys

- ingramWinterGreen_Legal

- CorruptHighCourtJudges

- LondonJewishMafia

- AncientAmerica-TheOlmecs

- Diana-Remembered-Part3

- Diana-Remembered-Part1

- Diana-Remembered-Part2

- Diana-Remembered-Part4

- BilderbergGroupHistory1

- Diana-Remembered-Part4

- RothschildZionistPromise

- CIASetUpJullianAssange

- IlluminatiNewWorldOrder1

- IlluminatiNewWorldOrder2

- USEmbassyCablesPart1

- USEmbassyCablesPart2

- USEmbassyCablesPart3

- LinbyaGadhafiNatostrikes

- AWNWorldNews_Dec_2008_P1

- MostPowerfulFamiiesPart1

- MostPowerfulFamiliesP2

- MostPowerfulFamiliesP3

- USAsLastNail_RonPaul

- USAPresidentsPart1

- USAPresidentsPart2

- USAPresidentInaugural1

- YahooNews_5_June2011

- YahooNews_6July_2011

- YahooNews_7July_2011

- NewsofTheWorld_ClosedP1

- NewsofTheWorld_Closed_P2

- Illuminati-History-Part1

- PresidentH.W&GW_Bush

- WillTheMurdochsgetJail

- INLWorldNewsJune2008

- YahooNews_10July_2011

- Illuminati-History-Part2

- Yahoo-INLNews_11July2011

- ScotlandYardWantsMurdoch

- AlexJones_NewMan_V_HuMan

- EdinburghFringeFest_2011

- JordonMaxwellWorldViews1

- AmyWinehouse_Dionne-Last

- JamesJoyce_MollyBloom

- INLNews_2008_History

- USAWeeklyNewsHistory2005

- ShaneBauer_JoshFattal

- INLNews_History-2010_P1

- HMLandRegistryCorruption

- UKRoyalCourtsOfInJustice

- Anti_Freemason-argument

- Leveson_Media_Inquiry

- PoliceFramed_Micklebergs

- CorruptJudges_CreditLaws

- Sodahead_Public_Opinion

- Australian_Media_Shakeup

- NewsFollowup_WorldNewsP1

- WhoMurderedThomasAllwood

- INLNews_Photos_June2012

- KatieHomesTomCruiseSpilt

- GoogleLinksThomasAllwood

- MurdochsOrderMediaBlock

- INLNewsPhotos_August2012

- USAPresident2008Election

- USANews_HillaryClintonP1

- USANews_Barack_Obama_P1

- USANews_Mitt_Romney_P1

- USANews_John_McCain_P1

- Trial_KyleMontgomery2012

- ReignofEvil_MindControl

- Page 112

- ClaremontSerialMurdersP1

- LenBuckeridge&SPKoh_BGC

- ClaremontSerialKillerCSK

- CSK_websleuths.com_P1

- CSK_websleuths.com_P2

- ClaremontSerialKillings2

- ClaremontSerialKillings3

- ClaremontSerialKillings4

- DavidCaporn_MallardCase1

- PoliceRoyalCommissionWA1

- WAPoliceCSK_Incompetance

- ClaremontSerialKillings5

- ArgyleDiamonds_WA_Police

- MissingMurdered_WestAust

- WestAustralianElections

- WestAustralianElections

- WesternAustralianPrisons

- MarkMcGowan_WAPremier

- KarlO'Callaghan_WAPolice

- RomualdZakHospitalMurder

- CrimeJustice_SubiacoPost

- AmandaForrester_DPPforWA

- MafiaAustraliaMurderDrug

- MafiaTriadGangsAustralia

- AustralianCrimeBossesP1

- RogerHughCookWestAustMLA

- BrendonOConnellSpeaksOut

- BrendonOconnell_TheTruth

- WAustralianPoliceHistory

- WesternAustralianHistory

- WorldW1AustralianHistory

- TaxExemptFoundationsDodd

- Zionist_Israel_MossadWeb

- HarcourtsRE_AdamSheilds

- AdolfHitlerFactsHistory

- SexDollsAreOfTheFuture

- StrangeEvents&Creatures1

- Business_Political_News1

- PrincessDianasMI5Murder1

- YRealEstate.asia

- ClaremontSerialKillerP5

- WA_NewPoliceCommissioner

- GeneGibson_SetUpByPolice

- IlluminatiExposedHistory

- NuganHandBank_CIA_Drugs

- BannedInBritain_VideosP1

- WebOfEvil_ElmGuestHouse1

- Latest_Updated_CSK_News1

- CIA-Control-of-Australia

- CIA_Terrorism_FalseFlags

- ShirleyFinnMurderInquest

- CSK-BradleyRobertEdwards

- LionelMurphy_AbeSaffron1

- Scientology_MI6_RootsP1

- Ron_Hubbard_GroomedByMI6

- Ron_Hubbard_MI6_Agent_P2

- Scientology_createdbyMI6

- IlluminatiMKUltraFormula

- MafiaAustraliaDrugMurder

- MKUltra_HypnoticTriggers

- MKUltra_LyingDeceitSkill

- Drug_Use_In_Mind_Control

- ClaremontSerialKillings6

- Gus_McCann_Irish_Singer

- Khashoggi_Slaying_ News

- Byron_Bay_NSW_Australia

- FreddieMercury_LifeTimes

- Death-of-Fairfax-MediaP1

- DrugDealers_&Informants1

- CanadianHolocaustHistory

- HowCIACreatedBinLaden-GL

- CarlyleGroupBCCI_Arbusto

- OperationMindControl_MKU

- Sociology_of_Sex_Work_P1

- Google_Bias_Investigated

- MovieStarsWhoHatedtoKiss

- RothchildCIASorosPuppets

- Royal_Kids_All_Grown_Up

- CelebrityKids_AllGrownUp

- CelebrityKids_NowGrownUp

- MarketMentalakaRantSpace

- BabyBlackSwanStudy-ByINL

- AWN_DailyNewsFeeds_P1

- YahooAWNNewsFeedsP1

- ReutersNewsFeedsP1

- AWNNews_Back_In_Time_P1

- AWNNews_WayBackInTime_P2

- AWNNews_WayBackInTime_P3

- AWNNews_WayBackInTime_P4

- CharlesMason_JohnWGacyP1

- SaudiWomenTryingToEscape

- ClaremontSerialKillings8

- MarquessofBlayne-Harlots

- DavidJCapornCorruptionP1

- DavidJCapornCorruptionP2

- SarahAnnMcMahonInquest

- ClaremontSerialKillings9

- How_prisoners_spend_Xmas

- IrishNews20thMarch2019

- TasmanianDevils_Survival

- Top30_MostBeautifulWomen

- ARTICHOKE_Project_Olson

- BIS_BankInternSettlement

- JulianAssange_ArrestedP1

- EconomicHitMan_Confess

- JulianAssangeArrestedP2.

- JulianAssangeArrested_P3

- JulianAssange_Arrest_P4

- TriumphOfTruthBookStolen

- MI6_James_Casbolt_Speaks

- MI6_CIA_Mossad_ASIO_KGB

- Kanopy_Documentary_Films

- Assange_Snowden_Files_P1

- EdwardSnowden_AssangeP.2

- Ron_Hubbard_Scientology1

- Ron_Hubbard_Scientology2

- Bear_Faced_Massiah_LRH1

- BearFacedMessiah_LRH_P2

- Scientology_RonHubbardP5

- Mary_Sue_Hubbard_Story_1

- SecretBasesOnPlanetEarth

- Woodstock_Festival_1969

- AnnieJacobsen_USA_Author

- FailCompilation_July2016

- GreatPerthMintSwindleP1

- Corvid_19_Exposed

INLNews USAWeeklyNewsNews Easy To find Hard To Leave EdinburghFringeFest USAWeekendNews.com

GMail HotMail MyWayMail AOLMail YahooMail GMail USA MAIL ReutersNewsVideos inl.org inl.gov inl.co.nz

INLNs CNNWorld IsraelVideoNs NYTimes WashNs WorldMedia JapaNs AusNs WorldVideoNs WorldFinanceChinaDaily IndiaNs

USADaily BBC EuroNs A

AdeaideNews TasNews ABCTas DarwinN Top Stories Video/Audio Reuters AP AFP The Christian Science Monitor U.S. News & World Report AFP Features Reuters Life! NPR The Advocate Pew Daily Number Today in History Obituaries Corrections Politics LocalNews o BBC News Video Reuters Video AFP Video CNBC Video Australia 7 News Video CBC.ca Video NPR Audio Kevin Sites in the Hot Zone Video Richard Bangs Adventures Video Charlie Rose Video Expanded Books Video Assignment Earth Video ROOFTOPCOMEDY.com Video Guinness World Records Video weather.com

AdolfHitlerFactsHistory

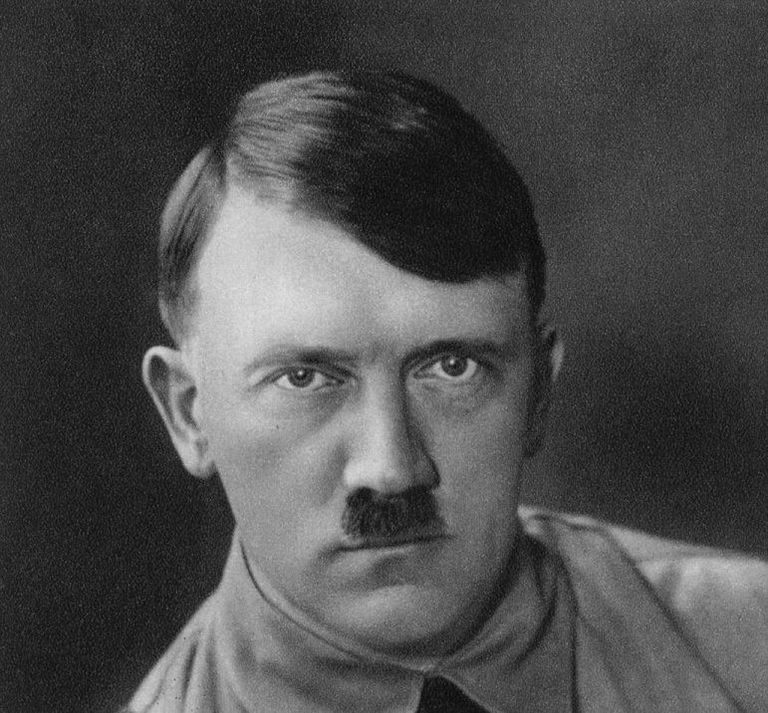

Adolf Hitler

34 Facts About Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (1889 - 1945) in Munich in the spring of 1932. Heinrich Hoffmann/Archive Photos/Getty Images

https://www.thoughtco.com/facts-about-hitler-1779642

Updated April 13, 2017

Nazi leader Adolf Hitler is known for being one of the most evil people in all of history. Responsible for starting World War II and the Holocaust, Hitler was a charismatic leader that successfully convinced the German people to follow his beliefs.

Below are 34 facts that take you from Hitler's birth in 1889 to his suicide in 1945.

HITLER'S FAMILY

- Despite becoming the dictator of Germany, Hitler was not born there. Hitler was born in Braunau am Inn, Austria on April 20, 1889.

- 1903) and Klara (1860-1907) Hitler.

- Hitler had only one sibling that survived childhood, Paula (1896-1960).

- However, Hitler also had four other siblings that died in childhood: Gustav (1885-1887), Ida (1886-1888), Otto (1887), and Edmund (1894-1900).

- In addition to his sister Paula, Hitler had one half brother, Alois (1882-1956) and one half sister, Angela (1883-1949), both from his father's previous marriage.

- Hitler was known as "Adi" in his youth.

- Hitler's father, Alois, was in his third marriage and 51 years old when Hitler was born. He was known as a strict man who retired from the civil service when Hitler was only 6. Alois died when Hitler was 13.

ARTIST AND ANTI-SEMITE

- Throughout his youth, Hitler dreamed of becoming an artist. He applied twice to the Vienna Academy of Art (once in 1907 and again in 1908) but was denied entrance both times.

- At the end of 1908, Hitler's mother died of breast cancer.

- After his mother's death, Hitler spent four years living on the streets of Vienna, selling postcards of his artwork to make a little money.

- No one is quite sure where or how Hitler picked up his virulent antisemitism. Some say it was because of the questionable identity of his grandfather (was Hitler's grandfather Jewish?). Others say Hitler was furious at a Jewish doctor that let his mother die. However, it is just as likely that Hitler picked up a hatred for Jews while living on the streets of Vienna, a city known at the time for its antisemitism.

HITLER AS A SOLDIER IN WORLD WAR I

- Although Hitler attempted to avoid Austrian military service by moving to Munich, Germany in May 1913, Hitler volunteered to serve in the German army once World War I began.

- Hitler endured and survived four years of World War I. During this time, he was awarded two Iron Crosses for bravery.

- Hitler sustained two major injuries during the war. The first occurred in October 1916 when he was wounded by a grenade splinter. The other was on October 13, 1918, when a gas attack caused Hitler to go temporarily blind.

- It was while Hitler was recovering from the gas attack that the armistice (i.e. the end of the fighting) was announced. Hitler was furious that Germany had surrendered and felt strongly that Germany had been "stabbed in the back" by its leaders.

HITLER ENTERS POLITICS

- Furious at Germany's surrender, Hitler returned to Munich after the end of World War I, determined to enter politics.

- In 1919, Hitler became the 55th member of a small antisemitic party called the German Worker's Party.

- Hitler soon became the party's leader, created a 25-point platform for the party, and established a bold red background with a white circle and swastika in the middle as the party's symbol. In 1920, the party's name was changed to National Socialist German Worker's Party (i.e. the Nazi Party).

- Over the next several years, Hitler often gave public speeches that gained him attention, followers, and financial support.

- In November 1923, Hitler spearheaded an attempt to take over the German government through a putsch (a coup), called the Beer Hall Putsch.

- When the coup failed, Hitler was caught and sentenced to five years in prison.

- It was while in Landsberg prison that Hitler wrote his book, Mein Kampf (My Struggle).

- After only nine months, Hitler was released from prison.

- After getting out of prison, Hitler was determined to build up the Nazi Party in order to take over the German government using legal means.

HITLER BECOMES CHANCELLOR

- In 1932, Hitler was granted German citizenship.

- In the July 1932 elections, the Nazi Party obtained 37.3 percent of the vote for the Reichstag (Germany's parliament), making it the controlling political party in Germany.

- On January 30, 1933, Hitler was appointed chancellor. Hitler then used this high-ranking position to gain absolute power over Germany. This finally happened when Germany's president, Paul von Hindenburg, died in office on August 2, 1934.

- Hitler took the title of Führer and Reichskanzler (Leader and Reich Chancellor).

HITLER AS FÜHRER

- As dictator of Germany, Hitler wanted to increase and strengthen the German army as well as expand Germany's territory. Although these things broke the terms of the Versailles Treaty, the treaty that officially ended World War I, other countries allowed him to do so. Since the terms of the Versailles Treaty had been harsh, other countries found it easier to be lenient than risk another bloody European war.

- In March 1938, Hitler was able to annex Austria into Germany (called the Anschluss) without firing a single shot.

- When Nazi Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, the other European nations could no longer stand idly by. World War II began.

- On July 20, 1944, Hitler barely survived an assassination attempt, called the July Plot. One of his top military officers had placed a suitcase bomb under the table during a conference meeting at Hitler's Wolf's Lair. Because the table leg blocked much of the blast, Hitler survived with only injuries to his arm and some hearing loss. Not everyone in the room was so lucky.

- On April 29, 1945, Hitler married his long-time mistress, Eva Braun.

- The following day, April 30, 1945, Hitler and Eva committed suicide together.

A Short Biography of Adolf Hitler

A print of Adolf Hitler from Kampf um's Dritte Reich: Historische Bilderfolge, Berlin, 1933. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

A print of Adolf Hitler from Kampf um's Dritte Reich: Historische Bilderfolge, Berlin, 1933. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Updated June 12, 2017

Adolf Hitler was the leader of Nazi Germany from his appointment as chancellor in 1933 until his suicide in 1945. Hitler was responsible for starting World War II and for killing more than 11 million people during the Holocaust.

Dates: April 20, 1889 -- April 30, 1945

Also Known As: Führer of the Third Reich

CHILDHOOD OF ADOLF HITLER

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, in Braunau am Inn, Austria.

his childhood in Austria. His father, Alois, retired from civil service in 1895 when Hitler was only six, which created a tense, strict atmosphere at home.

When Hitler was 13, his father passed away and his mother, Klara, had to care for Hitler and his siblings by herself. Times were tough for the Hitler household. In 1905, at age 16, Adolf quit school and never returned.

HITLER AS AN ARTIST

Hitler dreamed of becoming an artist, so in 1907 he applied to the painting school at the Vienna Academy of Art. He did not pass the entrance exam. After his mother passed away just a few months later from breast cancer, Hitler again tried to apply to the Vienna Academy of Art, but this time he was not even allowed to take the test.

Hitler spent the next four years in Vienna, living off what little he earned from selling postcards of his architectural drawings and the small inheritance from his mother.

During this period of time, Hitler started to dabble in politics and became especially influenced by pan-Germanism.

HITLER SERVES IN WORLD WAR I

To avoid military service in the Austrian army, Hitler moved to Munich, Germany in May 1913 but as soon as World War I broke out, Hitler asked for and received special permission to serve in the Bavarian-German army.

Adolf Hitler quickly proved to be a courageous soldier. By December 1914, he was awarded the Iron Cross (Second Class), in October 1916 he was wounded by a grenade splinter, and in August 1918 he was awarded the Iron Cross (First Class).

On October 13, 1918, a gas attack caused him to go temporarily blind. While recuperating in a hospital, Hitler heard the news of the end of the war and Germany's defeat. His anger and feelings of betrayal shaped his and the world's future.

HITLER GETS POLITICAL

After the war, many in Germany felt betrayed by the German government for their sudden and unexpected surrender. The subsequent inflation made even finding a job and day-to-day living difficult for the average German citizen.

In 1919, Hitler was working for an army organization in which he checked-up on burgeoning local political groups. While spying on these groups in September 1919, Hitler found one he liked. Soon after joining the group (he became the 55th member), he was leading it. The following year, the group was renamed Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP (the Nazi Party).

HITLER'S COUP

Hitler believed that he could provide a stronger government that would bring strength and prestige back to Germany.

So, on November 9, 1923, he attempted a coup of the government, the Beer Hall Putsch. It failed, and Hitler was sentenced to five years at Landsberg Prison.

Although Hitler only served nine months of his term, he used this time to formulate his thoughts about a new Germany, which he made into a book, Mein Kampf. Once he was released, Hitler continued on his road to ultimate power.

HITLER COMES TO POWER IN GERMANY

By July 1932, Hitler had enough support to run for president of Germany, though he lost the election to Paul von Hindenburg. However, on January 30, 1933, Hindenburg appointed Hitler as chancellor of Germany.

Within a year and a half, Hitler was able to take over both the position of president (Hindenburg died) and chancellor and combine them into one position of supreme leader, the Führer.

After legally gaining power in Germany, Hitler quickly began solidifying his position by putting those that disagreed with him into concentration camps. He created massive amounts of propaganda that strengthened German pride by blaming all their problems on Communists and Jews. The concept of pan-Germanism inspired Hitler to combine German peoples in various countries in Europe as well as look east for lebensraum.

HITLER STARTS WORLD WAR II

Since the world was extremely sensitive about the possibility of starting another world war, Hitler was able to annex Austria in 1938 without a single battle. But when he had his forces entered Poland in August 1939, the world could no longer stand aside and just watch -- World War II began.

From the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 to Kristallnacht in 1938, Hitler slowly removed Jews from German society. However, with the cover of World War II, the Nazis created an elaborate and intensive system to work Jews as slaves and kill them. Hitler is considered one of the most evil people in history because of the Holocaust.

During the beginning of World War II, the German war machine seemed unstoppable. However, the tide turned at the Battle of Stalingrad at the beginning of 1943. As the Allied Armies got closer to Berlin, Hitler continued to control his regime from the safety of an underground bunker. Soon, even that was no longer safe.

On April 29, 1945, Adolf Hitler married his long-time mistress, Eva Braun, and wrote both his last will and political testament. The following day, on April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide.

Adolf Hitler Biography

Leader of the Nazi Party, Infamous Dictator

https://www.thoughtco.com/adolf-hitler-biography-1221627

Adolf Hitler. (Wikimedia Commons)

by Robert Wilde

Updated June 19, 2017

Born: April 20, 1889, Braunau am Inn, Austria

Died: April 30, 1945, Berlin, by suicide

Adolf Hitler was leader of Germany during the Third Reich (1933 – 1945) and the primary instigator of both the Second World War in Europe and the mass execution of millions of people deemed to be "enemies" or inferior to the Aryan ideal. He rose from being a talentless painter to dictator of Germany and, for a few months, emperor of much of Europe, before the constant gambling approach which had led him that far now brought only disaster.

His empire was crushed by an array of the world's strongest nations, and he killed himself, having killed millions in turn.

CHILDHOOD

Adolf Hitler was born in Braunau am Inn, Austria, on April 20th 1889 to Alois Hitler (who, as an illegitimate child, had previously used his mother’s name of Schickelgruber) and Klara Poelzl. A moody child, he grew hostile towards his father, especially once the latter had retired and the family had moved to the outskirts of Linz. Alois died in 1903 but left money to take care of the family. Hitler was close to his mother, who was highly indulgent of Hitler, and he was deeply affected when she died in 1907. He left school at 16 in 1905, intending to become a painter. Unfortunately, he wasn't a very good one.

VIENNA

Hitler went to Vienna in 1907 where he applied to the Viennese Academy of Fine Arts but was twice turned down. This experience further embittered the increasingly angry Hitler, and he returned when his mother died, living first with a more successful friend (Kubizek), and then moving from hostel to hostel, a lonely, vagabond figure.

He recovered to make a living selling his art cheaply as a resident in a community 'Men's Home.' During this period, Hitler appears to have developed the worldviewthat would characterize his whole life: a hatred for Jews and Marxists. Hitler was well placed to be influenced by the demagogy of Karl Lueger, Vienna’s deeply anti-Semitic mayor and a man who used hate to help create a party of mass support.

Hitler had previously been influenced by Schonerer, an Austrian politician against liberals, socialists, Catholics, and Jews. Vienna was also highly anti-Semitic with a press extolling it: Hitler's hate was not unusual, it was simply part of the popular mindset. What Hitler went on to do was present these ideas as a whole and more successfully than ever before.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Hitler moved to Munich in 1913 and avoided Austrian military service in early 1914 by virtue of being unfit. However, when the First World War broke out in 1914, he joined the 16th Bavarian Infantry Regiment (an oversight prevented him from being sent to Austria), serving throughout the war, mostly as a corporal after refusing promotion. He proved to be an able and brave soldier as a dispatch runner, winning the Iron Cross on two occasions (First and Second Class). He was also wounded twice, and four weeks before the war ended suffered a gas attack which temporarily blinded and hospitalized him. It was there he learned of Germany’s surrender, which he took as a betrayal. He especially hated the Treaty of Versailles, which Germany had to sign after the war as part of the settlement. An enemy soldier once claimed he had a chance to kill Hitler during World War I.

HITLER ENTERS POLITICS

After WWI, Hitler became convinced he was destined to help Germany, but his first move was to stay in the army for as long as possible because it paid wages, and to do so, he went along with the socialists now in charge of Germany. He was soon able to turn the tables and drew the attention of army anti-socialists, who were setting up anti-revolutionary units. Had he not been picked out by one interested man, he may never have amounted to anything. In 1919, working for an army unit, he was assigned to spy on a political party of roughly 40 idealists called the German Workers Party. Instead, he joined it, swiftly rose to a position of dominance (he was chairman by 1921), and renamed it the Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). He gave the party the Swastika as a symbol and organized a personal army of ‘storm troopers’ (the SA or Brownshirts) and a bodyguard of black-shirted men, the SS, to attack opponents.

He also discovered, and used, his powerful ability for public speaking.

THE BEER HALL PUTSCH

In November 1923, Hitler organized Bavarian nationalists under a figurehead of General Ludendorff into a coup (or 'putsch'). They declared their new government in a beer hall in Munich and then 3000 marched through the streets, but they were met by police who opened fire, killing 16. It was a poorly thought out plan based mostly in the realms of fantasy and could have ended the career of the young man. Hitler was arrested and tried in 1924 but was sentenced to only five years in prison, a sentence often taken as a sign of tacit agreement with his views after a trial he'd used to spread his name and his ideas widely (with success). Hitler served only nine months in prison, during which he wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle), a book outlining his theories on race, Germany, and Jews. It sold five million copies by 1939. Only then, in prison, did Hitler come to believe he was the one who should be leader instead of just their drummer. A man who thought he was paving the way for a German leader of genius now thought he was the genius who could take and use power. He was only half right.

POLITICIAN

After the Beer-Hall Putsch, Hitler resolved to seek power through subverting the Weimar government system, and he carefully rebuilt the NSDAP, or Nazi, party, allying with future key figures like Goeringand propaganda mastermind Goebbels. Over time, he expanded the party’s support, partly by exploiting fears of socialists and partly by appealing to everyone who felt their economic livelihood threatened by the depression of the 1930s until he had the ears of big business, the press , and the middle classes. Nazi votes jumped to 107 seats in the Reichstag in 1930. It's important to stress that Hitler wasn't a socialist. The Nazi party that he was molding was based on race, not the class of socialism, but it took a good few years for Hitler to grow powerful enough to expel the socialists from the party.

Hitler didn't take power in Germany overnight, and he didn't take full power of his party overnight. Sadly, he did do both eventually.

PRESIDENT AND FÜHRER

In 1932, Hitler acquired German citizenship and ran for president, coming second to von Hindenburg. Later that year, the Nazi party acquired 230 seats in the Reichstag, making them the largest party in Germany. At first, Hitler was refused the office of Chancellor by a president who distrusted him, and a continued snub might have seen Hitler cast out as his support failed. However, factional divisions at the top of government meant that, thanks to conservative politicians believing they could control Hitler, he was appointed Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Hitler moved with great speed to isolate and expel opponents from power, shutting trade unions, removing communists, conservatives, and Jews.

Later that year, Hitler perfectly exploited an act of arson on the Reichstag (which some believe the Nazis helped cause) to begin the creation of a totalitarian state, dominating the March 5th elections thanks to support from nationalist groups. Hitler soon took over the role of president when Hindenburg died and merged the role with that of Chancellor to become Führer (‘Leader’) of Germany.

IN POWER

Hitler continued to move with speed in radically changing Germany, consolidating power, locking up “enemies” in camps, bending culture to his will, rebuilding the army, and breaking the constraints of the Treaty of Versailles. He tried to change the social fabric of Germany by encouraging women to breed more and bringing in laws to secure racial purity; Jews were particularly targeted. Employment, high elsewhere in a time of depression, fell to zero in Germany. Hitler also made himself head of the army, smashed the power of his former brownshirt street warriors, and expunged the socialists fully from his party and his state. Nazism was the dominant ideology. Socialists were the first in the camps.

WORLD WAR TWO AND THE FAILURE OF THE THIRD REICH

Hitler believed he must make Germany great again through creating an empire, and engineered territorial expansion, uniting with Austria in an anschluss, and dismembering Czechoslovakia. The rest of Europe was worried, but France and Britain were prepared to concede limited expansion: Germany taking within it the German fringe. Hitler, however, wanted more, and it was in September 1939 when German forces invaded Poland, that other nations took a stand, declaring war. This was not unappealing to Hitler, who believed Germany should make itself great through war, and invasions in 1940 went well, knocking France out. However, his fatal mistake occurred in 1941 with the invasion of Russia, through which he wished to create lebensraum, or ‘living room.’ After initial success, German forces were pushed back by Russia, and defeats in Africa and West Europe followed as Germany was slowly beaten. During this time, Hitler became gradually more paranoid and divorced from the world, retreating to a bunker. As armies approached Berlin from two directions, Hitler married his mistress, Eva Braun, and on April 30, 1945, killed himself. The Soviets found his body soon after and spirited it away so it would never become a memorial. A piece remains in a Russian archive.

HITLER AND HISTORY

Hitler will forever be remembered for starting the Second World War, the most costly conflict in world history, thanks to his desire to expand Germany’s borders through force. He will equally be remembered for his dreams of racial purity, which prompted him to order the execution of millions of people, perhaps as high as eleven million. Although every arm of German bureaucracy was turned to pursuing the executions, Hitler was the chief driving force.

MENTALLY ILL?

In the decades since Hitler’s death, many commentators have concluded that he must have been mentally ill and that, if he wasn’t when he started his rule, the pressures of his failed wars must have driven him mad. Given that he ordered genocide and ranted and raved, it is easy to see why people have come to this conclusion, but it’s important to state that there is no consensus among historians that he was insane, or what psychological problems he may have had.

Ireland's Nazis - Episode One - Andrija Artuković (2007)

Published on Nov 28, 2013

SUBSCRIBE 980

Winner of the Globe Gold Award (Documentary section) at the Intermedia World Media Festival in Hamburg, this two part series sees RAF veteran Cathal O'Shannon uncover the truth about the war criminals and collaborators who found refuge in Ireland in the years after World War 2. O'Shannon begins with an investigation into the notorious Andrija Artukovic, Nazi Minister of the Interior in Croatia and the man responsible for the deaths of over 1,000,000 men, women and children in concentration camps. His time here is shrouded in mystery, as the Department of Foreign Affairs still refuses to release the file on this man. Programme One also focuses on Celestine Laine, leader of the Bezen Perrot, a Waffen SS unit responsible for the torture and murder of civilians in occupied Brittany, and Pieter Menten, responsible for the deaths of hundreds of Jews in Poland. Why was the Irish state prepared to harbour men such as Artukovic and Laine, while Jewish refugees were refused asylum? To find out the answer, Cathal talks to historians and other experts, uncovers government documents, and investigates the thorny issue of anti-Semitism in mid-20th century Ireland. Broadcasters - Canada Tv , History Channel Hd Uk , RTÉ Official site - http://tilefilms.ie/productions/irela...

The Nazis

A Short History of the Nazi Party

https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-the-nazi-party-1779

Adolf Hitler poses with a group of Nazis soon after his appointment as Chancellor. (Picture courtesy of USHMM Photo Archives.)

by Jennifer L. Goss, Contributing Writer

March 29, 2016

The Nazi Party was a political party in Germany, led by Adolf Hitler from 1921 to 1945, whose central tenets included the supremacy of the Aryan people and blaming Jews and others for the problems within Germany. These extreme beliefs eventually led to World War II and the Holocaust. At the end of World War II, the Nazi Party was declared illegal by the occupying Allied Powers and officially ceased to exist in May 1945.

(The name “Nazi” is actually a shortened version of the party’s full name: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP, which translates to “National Socialist German Workers’ Party.”)

Party Beginnings

In the immediate post-World-War-I period, Germany was the scene of widespread political infighting between groups representing the far left and far right. The Weimar Republic (the name of the German government from the end of WWI to 1933) was struggling as a result of its tarnished birth accompanied by the Treaty of Versailles and the fringe groups sought to take advantage of this political unrest.

It was in this environment that a locksmith, Anton Drexler, joined together with his journalist friend, Karl Harrer, and two other individuals (journalist Dietrich Eckhartand German economist Gottfried Feder) to create a right-wing political party, the German Workers’ Party, on January 5, 1919.

The party’s founders had strong anti-Semitic and nationalist underpinnings and sought to promote a paramilitary Friekorps culture that would target the scourge of communism.

Adolf Hitler Joins the Party

After his service in the German Army (Reichswehr) during World War I, Adolf Hitler had difficulty re-integrating into civilian society.

He eagerly accepted a job serving the Army as a civilian spy and informant, a task that required him to attend meetings of German political parties identified as subversive by the newly formed Weimar government.

This job appealed to Hitler, particularly because it allowed him to feel that was still serving a purpose to the military for which he would have eagerly given his life. On September 12, 1919, this position took him to a meeting of the German Worker’s Party (DAP).

Hitler’s superiors had previously instructed him to remain quiet and simply attend these meetings as a non-descript observer, a role he was able to accomplish with success until this meeting. Following a discussion on Feder’s views against capitalism, an audience member questioned Feder and Hitler quickly rose to his defense.

No longer anonymous, Hitler was approached after the meeting by Drexler who asked Hitler to join the party. Hitler accepted, resigned from his position with the Reichswehr and became member #555 of the German Worker’s Party. (In reality, Hitler was the 55th member, Drexler added the 5 prefix to the early membership cards to make the party appear larger than it was in those years.)

Hitler Becomes Party Leader

Hitler quickly became a force to be reckoned with in the party. He was appointed to be a member of the party’s central committee and in January 1920, he was appointed by Drexler to be the party’s Chief of Propaganda.

A month later, Hitler organized a party rally in Munich that was attended by over 2000 people. Hitler made a famous speech at this event outlining the newly created, 25-point platform of the party. This platform was drawn up by Drexler, Hitler, and Feder. (Harrer, feeling increasingly left out, resigned from the party in February 1920.)

The new platform emphasized the party’s volkisch nature of promoting a unified national community of pure Aryan Germans. It placed blame for the nation’s struggles on immigrants (mainly Jews and Eastern Europeans) and stressed excluding these groups from the benefits of a unified community that thrived under nationalized, profit-sharing enterprises instead of capitalism.

The platform also called for over-turning the tenants of the Treaty of Versailles, and re-instating the power of the German military that Versailles had severely restricted.

With Harrer now out and the platform defined, the group decided to add in the word “Socialist” into their name, becoming the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP) in 1920.

Membership in party rose rapidly, reaching over 2,000 registered members by the end of 1920. Hitler’s powerful speeches were credited with attracting many of these new members. It was because of his impact that party members were deeply troubled by his resignation from the party in July 1921 following a movement within the group to merge with the German Socialist Party (a rival party who had some overlapping ideals with the DAP).

When the dispute was resolved, Hitler rejoined the party at the end of July and was elected party leader two days later on July 28, 1921.

Beer Hall Putsch

Hitler’s influence on the Nazi Party continued to draw members. As the party grew, Hitler also began to shift his focus more strongly towards antisemitic views and German expansionism.

Germany’s economy continued to decline and this helped increase party membership. By the fall of 1923, over 20,000 people were members of the Nazi Party. Despite Hitler’s success, other politicians within Germany did not respect him. Soon, Hitler would take action that they could not ignore.

In the fall of 1923, Hitler decided to take the government by force through a putsch (coup). The plan was to first take over the Bavarian government and then the German federal government.

On November 8, 1923, Hitler and his men attacked a beer hall where Bavarian-government leaders were meeting. Despite the element of surprise and machine guns, the plan was soon foiled. Hitler and his men then decided to march down the streets but were soon shot at by the German military.

The group quickly disbanded, with a few dead and a number injured.

Hitler was later caught, arrested, tried, and sentenced to five years at Landsberg Prison. Hitler, however, only served eight months, during which time he wrote Mein Kampf.

As a result of the Beer Hall Putsch, the Nazi Party was also banned in Germany.

The Party Begins Again

Although the party was banned, members continued to operate under the mantle of the “German Party” between 1924 and 1925, with the ban officially ending on February 27, 1925. On that day, Hitler, who had been released from prison in December 1924, re-founded the Nazi Party.

With this fresh start, Hitler redirected the party’s emphasis toward strengthening their power via the political arena rather than the paramilitary route. The party also now had a structured hierarchy with a section for “general” members and a more elite group known as the “Leadership Corps.” Admission into the latter group was through special invitation from Hitler.

The party re-structuring also created a new position of Gauleiter, which were regional leaders that were tasked with building party support in their specified areas of Germany. A second paramilitary group was also created, the Schutzstaffel (SS), which served as the special protection unit for Hitler and his inner circle.

Collectively, the party sought success via the state and federal parliamentary elections, but this success was slow to come to fruition.

National Depression Fuels Nazi Rise

The burgeoning Great Depression in the United States soon spread throughout the world. Germany was one of the worst countries to be affected by this economic domino effect and the Nazis benefitted from the rise in both inflation and unemployment in the Weimar Republic.

These problems led Hitler and his followers to begin a broader campaign for public support of their economic and political strategies, blaming both the Jews and communists for their country’s backward slide.

By 1930, with Joseph Goebbels working as the party’s chief of propaganda, the German populace was really starting to listen to Hitler and the Nazis.

In September 1930, the Nazi Party captured 18.3% of the vote for the Reichstag (German parliament). This made the party the second-most influential political party in Germany, with only the Social Democratic Party holding more seats in the Reichstag.

Over the course of the next year and a half, the Nazi Party’s influence continued to grow and in March 1932, Hitler ran a surprisingly successful presidential campaign against aged World War I hero, Paul Von Hindenburg. Although Hitler lost the election, he captured an impressive 30% of the vote in the first round of the elections, forcing a run-off election during which he captured 36.8%.

Hitler Becomes Chancellor

The Nazi Party’s strength within the Reichstag continued to grow following Hitler’s presidential run. In July 1932, an election was held following a coup on the Prussian state government. The Nazis captured their highest number of votes yet, winning 37.4% of the seats in the Reichstag.

The party now held the majority of the seats in the parliament. The second largest party, the German Communist Party (KPD), held only 14% of the seats. This made it difficult for the government to operate without the support of a majority coalition. From this point forward, the Weimar Republic began a rapid decline.

In an attempt to rectify the difficult political situation, Chancellor Fritz von Papen dissolved the Reichstag in November 1932 and called for a new election. He hoped that support for both of these parties would drop below 50% total and that the government would then be able to form a majority coalition to strengthen itself.

Although the support for the Nazis did decline to 33.1%, the NDSAP and KDP still retained over 50% of the seats in the Reichstag, much to Papen’s chagrin. This event also fueled the Nazis’ desire to seize power once and for all, and set in motion the events that would lead to Hitler’s appointment as chancellor.

A weakened and desperate Papen decided that his best strategy was to elevate the Nazi leader to the position of chancellor so that he, himself, could maintain a role in the disintegrating government. With the support of media magnet Alfred Hugenberg, and new chancellor Kurt von Schleicher, Papen convinced President Hindenburg that placing Hitler into the role of chancellor would be the best way to contain him.

The group believed that if Hitler were given this position then they, as members of his cabinet, could keep his right-wing policies in check. Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to the political maneuvering and on January 30, 1933, officially appointed Adolf Hitler as the chancellor of Germany.

The Dictatorship Begins

On February 27, 1933, less than a month after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor, a mysterious fire destroyed the Reichstag building. The government, under the influence of Hitler, was quick to label the fire arson and place the blame on the communists.

Ultimately, five members of the Communist Party were put on trial for the fire and one, Marinus van der Lubbe, was executed in January 1934 for the crime. Today, many historians believe that the Nazis set the fire themselves so that Hitler would have a pretense for the events that followed the fire.

On February 28, at the urging of Hitler, President Hindenburg passed the Decree for the Protection of the People and the State. This emergency legislation extended the Decree for the Protection of the German People, passed on February 4. It largely suspended the civil liberties of the German people claiming that this sacrifice was necessary for personal and state safety.

Once this “Reichstag Fire Decree” was passed, Hitler used it as an excuse to raid the offices of the KPD and arrest their officials, rendering them nearly useless despite the results of the next election.

The last “free” election in Germany took place on March 5, 1933. In that election, members of the SA flanked the entrances of polling stations, creating an atmosphere of intimidation that led to the Nazi Party capturing their highest vote total to-date, 43.9% of the votes.

The Nazis were followed in the polls by the Social Democratic Party with 18.25% of the vote and the KPD, which received 12.32% of the vote. It was not surprising that the election, which occurred as a result of Hitler’s urging to dissolve and reorganize the Reichstag, garnered these results.

This election was also significant because the Catholic Centre Party captured 11.9% and the German National People’s Party (DNVP), led by Alfred Hugenberg, won 8.3% of the vote. These parties joined together with Hitler and the Bavarian People’s Party, which held 2.7% of the seats in the Reichstag, to create the two-thirds majority that Hitler needed to pass the Enabling Act.

Enacted on March 23, 1933, the Enabling Act was one of the final steps on Hitler’s path to becoming a dictator; it amended the Weimar constitution to allow Hitler and his cabinet to pass laws without Reichstag approval.

From this point forward, the German government functioned without input from the other parties and the Reichstag, which now met in the Kroll Opera House, was rendered useless. Hitler was now fully in control of Germany.

World War II and the Holocaust

Conditions for minority political and ethnic groups continued to deteriorate in Germany. The situation worsened after President Hindenburg’s death in August 1934, which allowed Hitler to combine the positions of president and chancellor into the supreme position of Führer.

With the official creation of the Third Reich, Germany was now on a path to war and attempted racial domination. On September 1, 1939 Germany invaded Poland and World War II began.

As the war spread throughout Europe, Hitler and his followers also increased their campaign against European Jewry and others that they had deemed undesirable. Occupation brought a large amount of Jews under German control and as a result, the Final Solution was created and implemented; leading to the death of over six million Jews and five million others during an event known as the Holocaust.

Although the events of the war initially went in Germany’s favor with the use of their powerful Blitzkrieg strategy, the tide changed in the winter of early 1943 when the Russians stopped their Eastern progress at the Battle of Stalingrad.

Over 14 months later, German prowess in Western Europe ended with the Allied invasion at Normandy during D-Day. In May 1945, just eleven months after D-day, the war in Europe officially ended with the defeat of Nazi Germany and the death of its leader, Adolf Hitler.

Conclusion

At the end of World War II, the Allied Powers officially banned the Nazi Party in May 1945. Although many high-ranking Nazi officials were put on trial during a series of post-war trials in the years following the conflict, the vast majority of rank and file party members were never prosecuted for their beliefs.

Today, the Nazi party remains illegal in Germany and several other European countries, but underground Neo-Nazi units have grown in number. In America, the Neo-Nazi movement is frowned upon but not illegal and it continues to attract members.

Ancestry of Adolf Hitler

Hitler's Last Name Was Almost Schicklgruber

https://www.thoughtco.com/ancestry-of-adolf-hitler-1779644

June 16, 2017

Adolf Hitler is a name that will forever be remembered in world history. He not only started World War II but was responsible for the deaths of 11 million people.

At the time, Hitler's name sounded fierce and strong, but what would have happened if Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's name had actually been Adolf Schicklgruber? Sound farfetched? You may not believe how close Adolf HItler was to carrying this somewhat comical sounding last name.

"HEIL SCHICKLGRUBER!"???

The name of Adolf Hitler has inspired both admiration and mortal dread. When Hitler became the Führer (the leader) of Germany, the short, powerful word "Hitler" not only identified the man who carried it, but the word turned into a symbol of strength and loyalty.

During Hitler's dictatorship, "Heil Hitler" became more than the pagan-like chant at rallies and parades, it became the common form of address. During these years, it was common to answer the telephone with "Heil Hitler" rather than the customary "Hello." Also, instead of closing letters with "Sincerely" or "Yours truly" one would write "H.H." - short for "Heil Hitler."

Would a last name of "Schicklgruber" have had the same, powerful effect?

ADOLF'S FATHER, ALOIS

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889 in the town of Braunau am Inn, Austria to Alois and Klara Hitler. Adolf was the fourth of six children born to Alois and Klara, but only one of two to survive childhood.

Adolf's father, Alois, was nearing his 52nd birthday when Adolf was born but was only celebrating his 13th year as a Hitler. Alois (Adolf's father) was actually born as Alois Schicklgruber on June 7, 1837 to Maria Anna Schicklgruber.

At the time of Alois' birth, Maria was not yet married. Five years later (May 10, 1842), Maria Anna Schicklgruber married Johann Georg Hiedler.

SO WHO WAS ALOIS' REAL FATHER?

The mystery concerning Adolf Hitler's grandfather (Alois' father) has spawned a multitude of theories that range from possible to preposterous. (Whenever beginning this discussion, one should realize that we can only speculate about this man's identity because the truth rested with Maria Schicklgruber, and as far as we know, she took this information to the grave with her in 1847.)

Some people have speculated that Adolf's grandfather was Jewish. If Adolf Hitler ever thought that there was Jewish blood in his own ancestry, some believe that this could explain Hitler's anger and treatment of Jews during the Holocaust. However, there is no factual basis for this speculation.

The simplest and legal answer to Alois' paternity points to Johann Georg Hiedler — the man Maria married five years after Alois' birth. The sole basis for this information dates to Alois' baptismal registry that shows Johann Georg claiming paternity over Alois on June 6, 1876 in front of three witnesses.

At first glance, this seems like reliable information until you realize that Johann Georg would have been 84 years old and had actually died 19 years earlier.

WHO CHANGED THE BAPTISMAL REGISTRY?

There are many possibilities to explain the change of registry, but most of the stories point the finger at Johann Georg Hiedler's brother, Johann von Nepomuk Huetler.

(The spelling of the last name was always changing - the baptismal registry spells it "Hitler.")

Some rumors say that because Johann von Nepomuk had no sons to carry on the name of Hitler, he decided to change Alois' name by claiming that his brother had told him that this was true. Since Alois had lived with Johann von Nepomuk for most of his childhood, it is believable that Alois seemed like his son.

Other rumors claim that Johann von Nepomuk was himself Alois' real father and that in this way he could give his son his last name.

No matter who changed it, Alois Schicklgruber officially became Alois Hitler at 39 years of age. Since Adolf was born after this name change, Adolf was born Adolf Hitler.

But isn't it interesting how close Adolf Hitler's name was to being Adolf Schicklgruber?

Ireland's Nazis - Episode Two - Otto "Scarface" Skorzeny (2007)

Published on Nov 28, 2013

SUBSCRIBE 980

Winner of the Globe Gold Award (Documentary section) at the Intermedia World Media Festival in Hamburg, this two part series sees RAF veteran Cathal O'Shannon uncover the truth about the war criminals and collaborators who found refuge in Ireland in the years after World War 2. In Programme Two, Cathal O'Shannon investigates how the cold war opened new channels for Nazis seeking sanctuary here. He tells the story of 'the most dangerous man in Europe' and Hitler's favourite soldier - Otto "Scarface" Skorzeny, a James Bond figure who famously rescued Mussolini from a mountaintop fortress. Skorzeny was feted by the Dublin social glitterati, even hobnobbing with a future Taoiseach. He also looks at Helmut Clissmann, the man tasked by the Nazis to recruit the IRA for their war against Britain. Cathal moves on to investigate the Flemish nationalists who became Nazi collaborators - men like Albert Folens, who went on to become a successful publisher of Irish schoolbooks, Albert Luykx, who fled justice in Belgium and later conspired with Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney to import arms for the IRA, and Staf Van Velthoven, the last surviving of 'Ireland's Nazis'. Broadcasters - Canada Tv , History Channel Hd Uk , RTÉ Official site - http://tilefilms.ie/productions/irela...

Adolf Hitler Appointed Chancellor of Germany

January 30, 1933

https://www.thoughtco.com/adolf-hitler-appointed-chancellor-of-germany-1779275

Adolf Hitler Appointed Chancellor of Germany

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

by Jennifer L. Goss, Contributing Writer

Updated June 16, 2017

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed as the chancellor of Germany by President Paul Von Hindenburg. This appointment was made in an effort to keep Hitler and the Nazi Party “in check”; however, it would have disastrous results for Germany and the entire European continent.

In the year and seven months that followed, Hitler was able to exploit the death of Hindenburg and combine the positions of chancellor and president into the position of Führer, the supreme leader of Germany.

STRUCTURE OF THE GERMAN GOVERNMENT

At the end of World War I, the existing German government under Kaiser Wilhelm II collapsed. In its place, Germany’s first experiment with democracy, known as the Weimar Republic, commenced. One of the new government’s first actions was to sign the controversial Treaty of Versailles which placed blame for WWI solely upon Germany.

The new democracy was primarily composed of the following:

- A president, who was elected every seven years and vested with immense powers.

- A chancellor, who was appointed by the president to oversee the Reichstag (Germany's parliament). The chancellor was frequently a member of the majority party in the Reichstag.

- The Reichstag consisted of members elected every four years and based on proportional representation (i.e. the number of seats was based on the number of votes received by each party).

Although this system put more power in the hands of the people than ever before, it was relatively unstable and would ultimately lead to the rise of one of the worst dictators in modern history.

HITLER’S RETURN TO GOVERNMENT

After his imprisonment for the failed 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler was outwardly reluctant to return as the leader of the Nazi Party; however, it did not take long for party followers to convince Hitler that they needed his leadership once again.

With Hitler as leader, the Nazi Party gained over 100 seats in the Reichstag by 1930 and was viewed as a significant party within the German government.

Much of this success can be attributed to the party’s propaganda leader, Joseph Goebbels.

THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 1932

In the spring of 1932, Hitler ran against incumbent and WWI hero Paul von Hindenburg. The initial presidential election on March 13, 1932 was an impressive showing for the Nazi Party with Hitler receiving 30% of the vote. Hindenburg won 49% of the vote and was the leading candidate; however, he did not receive the absolute majority needed to be awarded the presidency. A run-off election was set for April 10.

Hitler gained over two million votes in the run-off, or approximately 36% of the total votes. Hindenburg only gained one million votes on his previous count but it was enough to give him 53% of the total electorate — enough for him to be elected to another term as president of the struggling republic.

THE NAZIS AND THE REICHSTAG

Although Hitler lost the election, the election results showed that the Nazi Party had grown both powerful and popular.

In June, Hindenburg used his presidential power to dissolve the Reichstag and appointed Franz von Papen as the new chancellor. As a result, a new election had to be held for the members of the Reichstag. In this July 1932 election, the popularity of the Nazi Party would be further affirmed with their massive gain of an additional 123 seats, making them the largest party in the Reichstag.

The following month, Papen offered his former supporter, Hitler, the position of Vice Chancellor. By this point, Hitler realized that he could not manipulate Papen and refused to accept the position. Instead, he worked to make Papen’s job difficult and aimed to enact a vote of no confidence. Papen orchestrated another dissolution of the Reichstag before this could occur.

In the next Reichstag election, the Nazis lost 34 seats. Despite this loss, the Nazis remained powerful. Papen, who was struggling to create a working coalition within the parliament, was unable to do so without including the Nazis. With no coalition, Papen was forced to resign his position of chancellor in November of 1932.

Hitler saw this as another opportunity to promote himself into the position of chancellor; however, Hindenburg instead appointed Kurt von Schleicher.

Papen was dismayed by this choice as he had attempted in the interim to convince Hindenburg to reinstate him as chancellor and allow him to rule by emergency decree.

A WINTER OF DECEIT

Over the course of the next two months, there was much political intrigue and backroom negotiations that occurred within the German government.

A wounded Papen learned of Schleicher’s plan to split the Nazi Party and alerted Hitler. Hitler continued to cultivate the support he was gaining from bankers and industrialists throughout Germany and these groups increased their pressure on Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as chancellor. Papen worked behind the scenes against Schleicher, who soon found out.

Schleicher, upon discovering Papen’s deceit, went to Hindenburg to request the President order Papen to cease his activities. Hindenburg did the exact opposite and encouraged Papen to continue his discussions with Hitler, as long as Papen agreed to keep the talks a secret from Schleicher.

A series of meetings between Hitler, Papen, and important German officials were held during the month of January. Schleicher began to realize that he was in a tenuous position and twice asked Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag and place the country under emergency decree. Both times, Hindenburg refused and on the second instance, Schleicher resigned.

HITLER IS APPOINTED CHANCELLOR

On January 29th, a rumor began to circulate that Schleicher was planning to overthrow Hindenburg. An exhausted Hindenburg decided that the only way to eliminate the threat by Schleicher and to end the instability within the government was to appoint Hitler as chancellor.

As part of the appointment negotiations, Hindenburg guaranteed Hitler that four important cabinet posts could be given to Nazis. As a sign of his gratitude and to offer reassurance of his professed good faith to Hindenburg, Hitler agreed to appoint Papen to one of the posts.

Despite Hindenburg’s misgivings, Hitler was officially appointed as chancellor and sworn in at noon on January 30, 1933.

Papen was named as his vice-chancellor, a nomination Hindenburg decided to insist upon to relieve some of his own hesitation with Hitler’s appointment.

Longtime Nazi Party member Hermann Göring was appointed in the dual roles of Minister of the Interior of Prussia and Minister Without Portfolio. Another Nazi, Wilhelm Frick, was named Minister of the Interior.

THE END OF THE REPUBLIC

Although Hitler would not become the Führer until Hindenburg’s death on August 2, 1934, the downfall of the German republic had officially begun.

Over the course of the next 19 months, a variety of events would drastically increase Hitler’s power over the German government and German military. It would only be a matter of time before Adolf Hitler attempted to assert his power over the entire continent of Europe.

The Brits Who Fought For Hitler

Published on Jun 15, 2011

FOR MORE GREAT DOCUMENTARIES GO TO www.DocumentaryList.NET "AND DONATE TO SUPPORT THE SITE ---- SORRY comments are disabled because of too many off topic flames ------ A nation reviles treachery, perhaps now more than ever. But the chronicles of recent history have ignored the most shameful episode of World War Two. The Britisches Freikorps unit of the Waffen SS served alongside the Nazis on the Eastern Front. Its members wore the death's head insignia and took German rank. They helped defend Berlin even as Hitler retreated to his bunker. But each and every member was recruited from British, Canadian, Australian and South African soldiers who volunteered to betray their country. Recognising the potential propaganda value of the unit, the Nazis ordered 800 SS uniforms with Union Jack arm badges. Most Allied prisoners of war ignored or resisted recruitment tactics ranging from leaflet bombardment to bribery and torture. But some 200 Allied prisoners answered the Nazi call. Some were motivated by greed, or by sympathies with the fascist cause. Others were simply described by intelligence files of the time as of 'weak character', and found the opportunities offered by the Germans to drink and womanise too tempting. The British Free Corps was itself betrayed by one of its number who joined only to feed MI5 with information. John Brown, the quartermaster of a camp at Genshagen. As Germany collapsed, Brown's information allowed the Allies to round up the traitors who often posed as fleeing PoWs. They were prosecuted and sentenced at court martial and treason trials. The intelligence files were quietly closed and access to the devastating information within was restricted. There was no cover-up, rather a conspiracy of indifference. For the first time on British Television, the British SS soldiers speak of their treachery, and their part in a failed German propaganda coup.

World War II Europe: The Road to War

Moving Towards Conflict

Benito Mussolini & Adolf Hitler, 1940. Photograph Courtesy of the National Archives & Records Administration

Updated August 29, 2016

World War II 101 | Next: The Phoney War to the Battle of Britain

EFFECTS OF THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES

Many of the seeds of World War II in Europe were sown by the Treaty of Versaillesthat ended World War I. In its final form, the treaty placed full blame for the war on Germany and Austria-Hungary, as well as exacted harsh financial reparations and led to territorial dismemberment. For the German people, who had believed that the armistice had been agreed to based on US President Woodrow Wilson's lenient Fourteen Points, the treaty caused resentment and a deep mistrust of their new government, the Weimar Republic.

The need to pay war reparations, coupled with the instability of the government, contributed to massive hyperinflation which crippled the German economy. This situation was made worse by the onset of the Great Depression.

In addition to the economic ramifications of the treaty, Germany was required to demilitarize the Rhineland and had severe limitations placed on the size of its military, including the abolishment of its air force. Territorially, Germany was stripped of its colonies and forfeited land for the formation the country of Poland. To ensure that Germany would not expand, the treaty forbade the annexation of Austria, Poland, and Czechoslovakia.

RISE OF FASCISM & THE NAZI PARTY

In 1922, Benito Mussolini and the Fascist Party rose to power in Italy. Believing in a strong central government and strict control of industry and the people, Fascism was a reaction to the perceived failure of free market economics and a deep fear of communism.

Highly militaristic, Fascism also was driven by a sense of belligerent nationalism that encouraged conflict as a means of social improvement. By 1935, Mussolini was able to make himself the dictator of Italy and transformed the country into a police state.

To the north in Germany, Fascism was embraced by the National Socialist German Workers Party, also known as the Nazis.

Swiftly rising to power in the late 1920s, the Nazis and their charismatic leader, Adolf Hitler, followed the central tenets of Fascism while also advocating for the racial purity of the German people and additional German Lebensraum (living space). Playing on the economic distress in Weimar Germany and backed by their "Brown Shirts" militia, the Nazis became a political force. On January 30, 1933, Hitler was placed in position to take power when he was appointed Reich Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg

THE NAZIS ASSUME POWER

A month after Hitler assumed the Chancellorship, the Reichstag building burned. Blaming the fire on the Communist Party of Germany, Hitler used the incident as an excuse to ban those political parties that opposed Nazi policies. On March 23, 1933, the Nazis essentially took control of the government by passing the Enabling Acts. Meant to be an emergency measure, the acts gave the cabinet (and Hitler) the power to pass legislation without the approval of the Reichstag. Hitler next moved to consolidate his power and executed a purge of the party (The Night of the Long Knives) to eliminate those who could threaten his position. With his internal foes in check, Hitler began the persecution of those who were deemed racial enemies of the state.

In September 1935, he passed the Nuremburg Laws which stripped Jews of their citizenship and forbade marriage or sexual relations between a Jew and an "Aryan." Three years later the first pogrom began (Night of Broken Glass) in which over one hundred Jews were killed and 30,000 arrested and sent to concentration camps.

GERMANY REMILITARIZES

On March 16, 1935, in clear violation of the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler ordered the remilitarization of Germany, including the reactivation of the Luftwaffe (air force). As the German army grew through conscription, the other European powers voiced minimal protest as they were more concerned with enforcing the economic aspects of the treaty. In a move that tacitly endorsed Hitler's violation of the treaty, Great Britain signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in 1935, which allowed Germany to build a fleet one third the size of the Royal Navy and ended British naval operations in the Baltic.

Two years after beginning the expansion of the military, Hitler further violated the treaty by ordering the reoccupation of the Rhineland by the German Army. Proceeding cautiously, Hitler issued orders that the German troops should withdrawal if the French intervened. Not wanting to become involved in another major war, Britain and France avoided intervening and sought a resolution, with little success, through the League of Nations. After the war several German officers indicated that if the reoccupation of the Rhineland had been opposed, it would have meant the end of Hitler's regime.

THE ANSCHLUSS

Emboldened by Great Britain and France's reaction to the Rhineland, Hitler began to move forward with a plan to unite all German-speaking peoples under one "Greater German" regime. Again operating in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler made overtures regarding the annexation of Austria. While these were generally rebuffed by the government in Vienna, Hitler was able to orchestrate a coup by the Austrian Nazi Party on March 11, 1938, one day before a planned plebiscite on the issue. The next day, German troops crossed the border to enforce the Anschluss (annexation). A month later the Nazis held a plebiscite on the issue and received 99.73% of the vote. International reaction was again mild, with Great Britain and France issuing protests, but still showing that they were unwilling to take military action.

World War II 101 | Next: The Phoney War to the Battle of Britain World War II 101 | Next: The Phoney War to the Battle of Britain

THE MUNICH CONFERENCE

With Austria in his grasp, Hitler turned towards the ethnically German Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. Since its formation at the end of World War I, Czechoslovakia had been wary of possible German advances. To counter this, they had built an elaborate system of fortifications throughout the mountains of the Sudetenland to block any incursion and formed military alliances with France and the Soviet Union.

In 1938, Hitler began supporting paramilitary activity and extremist violence in the Sudetenland. Following the Czechoslovakia's declaration of martial law in the region, Germany immediately demanded that the land be turned over to them.

In response, Great Britain and France mobilized their armies for the first time since World War I. As Europe moved towards war, Mussolini suggested a conference to discuss the future of Czechoslovakia. This was agreed to and the meeting opened in September 1938, at Munich. In the negotiations, Great Britain and France, led by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and President Édouard Daladier respectively, followed a policy of appeasement and caved to Hitler's demands in order to avoid war. Signed on September 30, 1938, the Munich Agreement turned over the Sudetenland to Germany in exchange for Germany's promise to make no additional territorial demands.

The Czechs, who had not been invited to conference, were forced to accept the agreement and were warned that if they failed to comply, they would be responsible for any war that resulted.

By signing the agreement, the French defaulted on their treaty obligations to Czechoslovakia. Returning to England, Chamberlain claimed to have achieved "peace for our time." The following March, German troops broke the agreement and seized the remainder of Czechoslovakia. Shortly thereafter, Germany entered into a military alliance with Mussolini's Italy.

THE MOLOTOV-RIBBENTROP PACT

Angered by what he saw as the Western Powers colluding to give Czechoslovakia to Hitler, Josef Stalin worried that a similar thing could occur with the Soviet Union. Though wary, Stalin entered into talks with Britain and France regarding a potential alliance. In the summer of 1939, with the talks stalling, the Soviets began discussions with Nazi Germany regarding the creation of a non-aggression pact. The final document, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, was signed on August 23, and called for the sale of food and oil to Germany and mutual non-aggression. Also included in the pact were secret clauses dividing Eastern Europe into spheres of influence as well as plans for the partition of Poland.

THE INVASION OF POLAND

Since World War I, tensions had existed between Germany and Poland regarding the free city of Danzig and the "Polish Corridor." The latter was a narrow strip of land reaching north to Danzig which provided Poland with access to the sea and separated the province of East Prussia from the rest of Germany. In an effort to resolve these issues and gain Lebensraum for the German people, Hitler began planning the invasion of Poland. Formed after World War I, Poland's army was relatively weak and ill-equipped compared to Germany.

To aid in its defense, Poland had formed military alliances with Great Britain and France.

Massing their armies along the Polish border, the Germans staged a fake Polish attack on August 31, 1939. Using this as a pretext for war, German forces flooded across the border the next day. On September 3, Great Britain and France issued an ultimatum to Germany to end the fighting. When no reply was received, both nations declared war.

In Poland, German troops executed a blitzkrieg (lightning war) assault using combining armor and mechanized infantry. This was supported from above by the Luftwaffe, which had gained experience fighting with the fascist Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). The Poles attempted to counterattack but were defeated at the Battle of Bzura (Sept. 9-19). As the fighting was ending at Bzura, the Soviets, acting on the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, invaded from the east.

Under assault from two directions, the Polish defenses crumbled with only isolated cities and areas offering prolonged resistance. By October 1, the country had been completely overrun with some Polish units escaping to Hungary and Romania. During the campaign, Great Britain and France, who were both slow to mobilize, provided little support to their ally.

With the conquest of Poland, the Germans implemented Operation Tannenberg which called for the arrest, detainment, and execution of 61,000 Polish activists, former officers, actors, and intelligentsia. By the end of September, special units known as Einsatzgruppen had killed over 20,000 Poles. In the east, the Soviets also committed numerous atrocities, including the murder of prisoners of war, as they advanced. The following year, the Soviets executed between 15,000-22,000 Polish POWs and citizens in the Katyn Forest on Stalin's orders.

World War II 101 | Next: The Phoney War to the Battle of Britain

Was Adolf Hitler a Socialist? Debunking a Historical Myth

by Robert Wilde

February 23, 2017

The Myth: Adolf Hitler, starter of World War 2 in Europe and driving force behind the Holocaust, was a socialist.

The Truth: Hitler hated socialism and communism and worked to destroy these ideologies. Nazism, confused as it was, was based on race, and fundamentally different from class focused socialism.

HITLER AS CONSERVATIVE WEAPON

Twenty-first century commentators like to attack left leaning policies by calling them socialist, and occasionally follow this up by explaining how Hitler, the mass murdering dictator around whom the twentieth century pivoted, was a socialist himself.

There’s no way anyone can, or ever should, defend Hitler, and so things like health-care reform are equated with something terrible, a Nazi regime which sought to conquer an empire and commit several genocides. The problem is, this is a distortion of history.

HITLER AS THE SCOURGE OF SOCIALISM

Richard Evans, in his magisterial three volume history of Nazi Germany, is quite clear on whether Hitler was a socialist: “…it would be wrong to see Nazism as a form of, or an outgrowth of, socialism.” (The Coming of the Third Reich, Evans, p. 173). Not only was Hitler not a socialist himself, nor a communist, but he actually hated these ideologies and did his utmost to eradicate them. At first this involved organizing bands of thugs to attack socialists in the street, but grew into invading Russia, in part to enslave the population and earn ‘living ‘ room for Germans, and in part to wipe out communism and ‘Bolshevism’.

The key element here is what Hitler did, believed and tried to create. Nazism, confused as it was, was fundamentally an ideology built around race, while socialism was entirely different: built around class. Hitler aimed to unite the right and left, including workers and their bosses, into a new German nation based on the racial identity of those in it.

Socialism, in contrast, was a class struggle, aiming to build a workers state, whatever race the worker was from. Nazism drew on a range of pan-German theories, which wanted to blend Aryan workers and Aryan magnates into a super Aryan state, which would involve the eradication of class focused socialism, as well as Judaism and other ideas deemed non-German.

When Hitler came to power he attempted to dismantle trade unions and the shell that remained loyal to him; he supported the actions of leading industrialists, actions far removed from socialism which tends to want the opposite. Hitler used the fear of socialism and communism as a way of terrifying middle and upper class Germans into supporting him. Workers were targeted with slightly different propaganda, but these were promises simply to earn support, to get into power, and then to remake the workers along with everyone else into a racial state. There was to be no dictatorship of the proletariat as in socialism; there was just to be the dictatorship of the Fuhrer.

The belief that Hitler was a socialist seems to have emerged from two sources: the name of his political party, the National Socialist German Worker’s Party, or Nazi Party, and the early presence of socialists in it.

THE NATIONAL SOCIALIST GERMAN WORKER’S PARTY

While it does look like a very socialist name, the problem is that ‘National Socialism’ is not socialism, but a different, fascist ideology. Hitler had originally joined when the party was called the German Worker’s Party, and he was there as a spy to keep an eye on it. It was not, as the name suggested, a devotedly left wing group, but one Hitler thought had potential, and as Hitler’s oratory became popular the party grew and Hitler became a leading figure.

At this point ‘National Socialism’ was a confused mishmash of ideas with multiple proponents, arguing for nationalism, anti-Semitism, and yes, some socialism. The party records don’t record the name change, but it’s generally believed a decision was taken to rename the party to attract people, and partly to forge links with other ‘national socialist’ parties.

The meetings began to be advertised on red banners and posters, hoping for socialists to come in and then be confronted, sometimes violently: the party was aiming to attract as much attention and notoriety as possible. But the name was not Socialism, but National Socialism and as the 20s and 30s progressed, this became an ideology Hitler would expound upon at length and which, as he took control, ceased to have anything to do with socialism.

‘NATIONAL SOCIALISM’ AND NAZISM