I, Barry Paul King, Coroner, having investigated the death of Sarah Jane Rutherford with an inquest held at the Perth Coroner’s Court, Court 51, CLC Building, 501 Hay Street, Perth, on 25 February 2014, find that the identity of the deceased person was Sarah Jane Rutherford and that death occurred on 27 December 2009 at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital from multiple injuries in the following circumstances:

Counsel Appearing:

Ms M. Smith assisting the Coroner

Ms R Hartley (State Solicitors Office) appearing on behalf of Graylands Hospital, Royal Perth Hospital and Broome Hospital

Table of Contents

Introduction ...................................................................................... 2

The Deceased .................................................................................... 4

Admisions at Graylands .................................................................... 6

Circumstances leading up to death .................................................... 9

Cause of death ................................................................................ 11

Manner of death .............................................................................. 11

Quality of supervision, treatment and care ...................................... 13

INTRODUCTION

1. Sarah Jane Rutherford (the deceased) died on 27 December 2009 after falling from an overpass onto the Mitchell Freeway in Hamersley while on leave from Graylands Hospital (Graylands).

2. As the deceased was an involuntary patient under the Mental Health Act 1996 at the time of her death, she was a ‘person held in care’ under section 3 of the Coroners Act 1996.

3. Section 22 (1)(a) of the Coroners Act 1996 provides that a coroner who has jurisdiction to investigate a death must hold an inquest if the death appears to be a Western Australian death and the deceased was immediately before death a person held in care.

4. An inquest to inquire into the death of the deceased was therefore mandatory.

5. Under s.25 (3) of the Coroners Act 1996, where a death investigated by a coroner is of a person held in care, the coroner must comment on the quality of the supervision, treatment and care of the person while in that care.

6. The death of the deceased was investigated together with the deaths of nine other persons who had been persons held in care as involuntary patients at Graylands under the Mental Health Act 1996 immediately before they died.

7. A joint inquest commenced before Coroner D.H. Mulligan in the Perth Coroner’s Court on 27 August 2012. Evidence was provided relating to the deaths of two of the other nine deceased persons.

The inquest was then adjourned until it recommenced on 11 March 2013 when evidence relevant to the deceased was adduced. On subsequent hearing days, evidence relevant to the remaining deceased persons and general evidence about

Graylands was provided to the Court. The hearings were completed on 22 April 2013.

8. Coroner Mulligan became unable to make findings under s.25 of the Coroners Act 1996, so I was directed by Acting State Coroner Evelyn Vicker to investigate the deaths.

9. To remove any doubt of my power to make findings under s.25, on 25 February 2014 I held another inquest into the death of the deceased. The evidence adduced in that inquest was that which had been obtained by Coroner Mulligan, including exhibits, materials and transcripts of audio recordings of the inquests. Interested parties who were present at the inquests before Coroner Mulligan were invited to make fresh or further submissions. All of the parties indicated their agreement with the appropriateness of the procedure I had adopted.

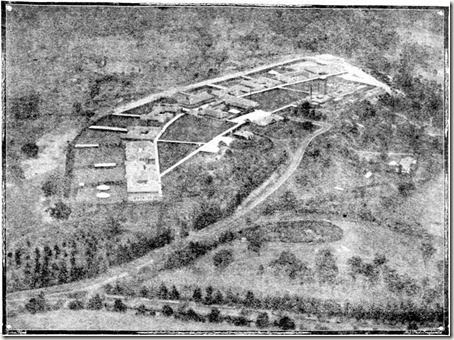

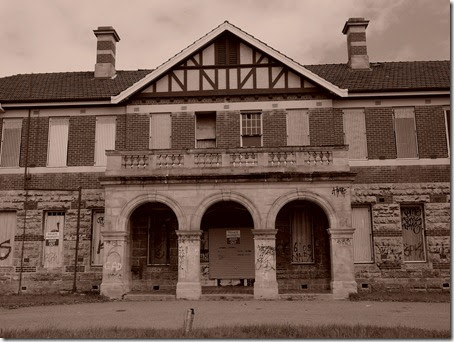

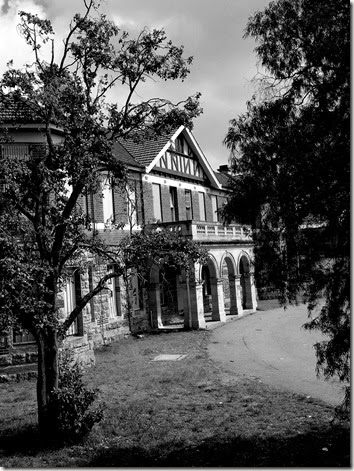

10. I should note that there was a great deal of evidence adduced at the inquest that was related to general or systemic issues pertinent to Graylands. That evidence was adduced to investigate whether those issues had a bearing on any or some of the deaths and to allow the court to comment on the quality of supervision, treatment and care of the deceased patients. For example, evidence of the condition of the buildings at Graylands containing wards was provided in order to allow the Court to investigate whether the physical environment of the wards would have been more therapeutic had the buildings been refurbished.

11. That general evidence was useful in providing an overview of the context in which the deceased persons were treated for their mental illnesses; however, in my view many of the issues the subject of that evidence were not sufficiently connected with all the respective deaths for me to comment on those issues under s.25 (2) or (3) of the Coroners Act 1996 generally as if they did.

12. I have therefore not addressed those general issues separately from a consideration of each death. Rather, where I have come to the view that the issues were potentially connected with the death or were relevant to the quality of the supervision, treatment and care of the deceased, I have addressed them in the respective findings.

THE DECEASED

13. The deceased was born on 22 August 1981 in Subiaco. She was the second of three girls and had a normal healthy childhood.

14. The deceased attended Catholic schools where she excelled academically and at sports. She was an avid reader, loved animals and held strong beliefs in human rights. She was socially active and generally healthy.1

15. In 1999, when studying for the Tertiary Entrance Examination (the TEE) in year 12, the deceased suffered a mental breakdown. She drove herself to her aunt’s home and her aunt took her to Cambridge Hospital where she was admitted for 12 days.2 It appears that the deceased had been using LSD and cannabis. She was thought to have had Bipolar II Disorder.3 She was discharged and appeared to have had no remaining evidence of the disorder.

She was transferred back to Graylands where she was admitted into Dorrington Ward, a secure, acute female-only ward.

16. However, about three months later the deceased was re-admitted to Cambridge Hospital for a week after being found unclothed and confused on City Beach. She had taken off her clothes in order to ‘surrender herself to go up to heaven’. On admission, she gave a history of depressed mood since the time she was discharged previously.4

17. The deceased was commenced on medication and she responded well.5

18. That year the deceased completed her TEE and went on to university where she studied towards a degree in Arts and a Bachelor of Education. About six months into her final year of study, the deceased was on her way to the country by car to do the practical component of teaching when she decided to return home and not complete her studies.6

19. She then took on a series of part-time jobs including working in a book store, in restaurants and as a gardener. She had lived away from home intermittently since she was 18 years old.

20. The deceased was involved in a relationship for about 12 months, during which she became pregnant. She had the pregnancy terminated and the termination had a strong adverse effect on her mental state.7

21. When she was about 23 years old, the deceased went to Korea where she worked as an English teacher for approximately seven months.8 She would regularly contact her parents, so when on one occasion they did not hear from her for about two days, her father contacted the Department of Foreign Affairs. Her repatriation was organised within 24 hours.9

22. When the deceased returned from Korea she was in a distressed mental state and had lost a lot of weight. Her parents took her to Joondalup Health Campus, but she refused to be admitted and the hospital could not admit her involuntarily.10 She went to live with her father.

23. A month or so later, the deceased suffered another mental breakdown. She told her father that life was not

worth living and that he should throw her under a car. Her father took her to Joondalup Health Campus, and this time she was admitted and eventually diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder with psychotic features. She remained in hospital for about two months

24. Over the next couple of years, the deceased managed to work and socialise with the help of medication prescribed by psychiatrists

ADMISSIONS AT GRAYLANDS

25. In late May 2007 the deceased was admitted to Graylands after being detained by police when she had taken off her clothes and had attempted to walk into the ocean at City Beach. She presented at Graylands perplexed and uncommunicative, and she attempted to assault nursing staff. She was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia with catatonic features.12

26. In the early part of this admission to Graylands, the deceased displayed bizarre behaviour consistent with experiencing hallucinations. She also exhibited features of catatonia including mutism, bizarre posturing and responding opposite to requests and directions.13

27. The deceased was treated with risperidone and lorazepam.

28. In June 2007 the deceased began to eat and drink normally and her mental condition began to improve. She was discharged on medication on 16 July 2007 and went to live with her mother in Duncraig.

29. For the next two years the deceased coped well with her condition. She worked at Spotlight, a large fabric and haberdashery shop and, apart from some signs of a relapse in May 2008, remained reasonably well. She

was under the ongoing care of a psychiatrist at the Osborne Adult Community Mental Health Service and began cognitive behavioural therapy and psycho-education with an occupational therapist there.

30. In early 2009 the deceased began to experience dark moods and tearful episodes though she continued to work at Spotlight. At this stage she was living with her younger sister. She had been taking an antidepressant and the dosage was increased at this time.

31. By about May 2009 the deceased had stopped taking the antidepressant and by September that year she was no longer experiencing psychotic symptoms. She was working 30 hours a week, exercising regularly, socialising through her church and seeing her parents. She got on well with her sister and was eating well. She was keen to stop taking antipsychotic medication, but agreed to stay on a reduced dose.15

32. On 9 November 2009 the deceased attended an appointment with her psychiatrist. She had stopped taking all her antipsychotic medication two weeks previously but had lost her appetite and her clarity of mind so had restarted her medication herself the day before the appointment. She appeared well at the time.

33. On 2 December 2009 the deceased was again found on a beach by police, who took her home. She asked her sister to obtain heroin for her so that she could overdose. Her sister called the Mental Health Emergency Response Line.16 The police returned and took the deceased to the emergency department at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital early the next morning. There she said that she had wanted the heroin to take away her pain

34. The deceased was diagnosed with a relapse of schizophrenia due to non-compliance with medication.

She was transferred back to Graylands where she was admitted into Dorrington Ward, a secure, acute female-only ward.

35. At Graylands the deceased initially denied any present self-harm or suicidal ideation, but on 4 December 2009 she told a psychiatrist that she believed that killing herself would make the world a better place. She was made an involuntary patient for her safety and put back on her medication.

36. Over the next few days the deceased began to settle and to socialise with other patients. She kept a low profile on the ward and was monitored every 30 minutes without incident. By 9 December 2009 she was keen to go back to work and was allowed to go for escorted walks on the hospital grounds.18

37. By 14 December 2009 the deceased was calm and settled and was able to carry on a sensible conversation. She was transferred to Plaistowe Ward, an open, mixed-gender rehabilitation ward where she settled in quickly. The next day she went Christmas shopping with her family without incident.19

38. On 17 December 2009 the deceased was given trial overnight leave with the expectation that she could progress to weekend leave shortly. That night the deceased’s aunt called Graylands by phone and expressed concern for the deceased’s mental state following conversations with her the previous day. She said that the deceased could mask her symptoms effectively if she had to.

39.

The next day, the deceased returned from overnight leave bright and rational. She was then granted weekend leave with plans for a review on Monday morning.

40. Over the weekend the deceased was quiet and withdrawn, struggling with finding her place in the world.20 By the time she returned to Graylands on Monday 21 December 2009, her mental health had deteriorated but she had no suicidal ideation. She was given leave to go home with her father and to return on Wednesday 23 December 2009 for review.21

41. The deceased returned to Graylands on 23 December 2009 for review by her psychiatrist as planned. Both she and her father told the psychiatrist that they thought that she was slowly improving. She denied any suicidal ideation and was keen to return to work the following week.

42. The psychiatrist assessed the deceased as only partly recovered from her psychotic episode but was still recovering slowly. He provided the deceased with a prescription for her medication and allowed her to return home with her father. In anticipation of recovery and discharge from Graylands, her psychiatrist made an appointment for her at the Osborne Adult Community Mental Health Service.22

43. On 24 December 2009 the deceased and her family travelled south to spend Christmas Day with her older sister. The day went well and the deceased participated in the family’s activities.23

44. On the way back to Perth on 26 December 2009, the family stopped in Mandurah to visit the deceased’s aunt and to go for a swim. The deceased was quiet on the return journey, but other members of the family were also quiet as they were tired from the festivities.

CIRCUMSTANCES LEADING UP TO DEATH

45. After the family had returned home, the deceased’s mother visited a neighbour for a drink. While there, she wedged her heel in some steps and injured her foot badly. When she went home, she was in pain and had to rest her foot in bed. The deceased helped to care for her later in the evening.24

46. The next morning, the deceased’s parents noted that the deceased was not home and that her bed did not appear to have been slept in. While they were concerned about her, the deceased’s mother was in great pain and her father had to take her to the emergency department at Joondalup Health Campus.

47. When they returned home, the deceased was not there. They noticed that her bicycle was not in its position in the shed. The deceased’s father drove around to search for the deceased and her mother rang Graylands to ask that the deceased be reported missing.25

48. In fact, at about 11.00pm on 26 December 2009 the deceased fell or jumped from a pedestrian bridge over the Mitchell Freeway between the Reid Highway and Beach Road and suffered non-survivable injuries.

49. Passersby stopped and rendered the deceased assistance. Stephanie Ellis, a nurse who had been driving south on the Mitchell Freeway, administered CPR until police arrived to assist.26

50. Ambulance paramedics arrived and conveyed the deceased to Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital with the help of a police officer who continued CPR in the back of the ambulance. The ambulance monitor indicated that the deceased initially had cardiac output, but that did not continue. CPR was maintained at hospital until it was clear that the deceased could not be revived. Her time of

death was recorded as 12.24am on 27 December 2009.

MANNER OF DEATH

51. On 30 December 2009 forensic pathologist Dr J McCreath conducted a post-mortem examination of the deceased’s body. The examination showed extensive fracturing of the skull and damage to the brain tissue, fracture of several ribs and blood in the chest cavities, bleeding within the soft tissues of the abdomen and fracture of the left wrist.28

CAUSE OF DEAT

52. Dr McCreath determined that the cause of death was multiple injuries, and I so find.

53. A toxicological analysis of the deceased’s blood and liver conducted as part of the post mortem investigation was negative for alcohol and common drugs.29

54. The Court obtained an opinion from clinical pharmacologist and toxicologist Professor David Joyce in relation to the time of the deceased’s last dose of her antipsychotic medication, risperidone.

55. Professor Joyce was only able to establish with any certainty that the deceased died more than about three hours from her most recent dose of risperidone. However, he said that the toxicological analysis did suggest that the deceased’s last dose was more than a day before she died.

56. On previous occasions the deceased’s mental state had deteriorated when she had stopped taking her medication, so it is possible that she became suicidal as

a result of not taking her medication in the day or days leading up to her death.

30 That she chose to die from falling onto a busy roadway was consistent with the incident after her return from Korea when she asked her father to throw her under a car in order to end her life.

57. The deceased gave her family no indication that she was contemplating suicide. Her father told the inquest, ‘ … we never, not in my wildest dreams did I think that would happen’.31 On the other hand, her mother noted that the deceased was clever enough to appear as though she was ok when in fact she was not,32 and her aunt made similar comments only 10 days before the death.33

58. The deceased’s bicycle was found on the bridge directly above the Mitchell Freeway where she was found. Reference to a street directory confirms that the bridge is well within bicycling distance from the deceased’s parents’ home, so it seems clear that that she rode her bicycle to the bridge.

59. In order to fall to the freeway from the bridge, the deceased had to climb over a concrete barrier on the side of the bridge, indicating that she had a clear intention to harm herself.

60. There was no evidence suggesting the involvement of another person in her fall to the freeway. There was no evidence to suggest that she was hit by a vehicle after she fell.

61. In these circumstances, I am satisfied that the deceased died as a result of injuries she suffered when she deliberately fell to the freeway with the intention of ending her life. I find that the manner of death was suicide.

QUALITY OF SUPERVISION, TREATMENT

AND CARE

62. On 3 December 2009 the deceased commenced her last admission in a confused and distressed state of mind. She had asked her sister to obtain heroin for her so that she could overdose, and she told her psychiatrist that killing herself would make the world a better place.34

63. After a few days being managed with antipsychotic medication on a secure ward with 30 minute visual observations for self harm, the deceased began to settle and to deny thoughts of self-harm. She became stable and rational with insight into her condition and the need for medication. She was allowed escorted ground access without incident and progressed to an open ward where she settled quickly.35 Nursing notes indicated that she appeared stable and compliant with the nursing care plan.36

64. On 15 December 2009 the deceased went shopping with her family and on 17 December 2009 she had overnight leave to stay with them. She then was allowed weekend leave. Her mental condition deteriorated during that weekend, but when she was reviewed on Monday 21 December 2009 there were no risk issues identified, so she was given leave to stay with her father with a review on 23 December 2009.37

65. At the review she appeared to be improved from her state on 21 December 2009. She denied any morbid thoughts or suicidal ideation. She was sleeping well and appeared to have no side-effects from her medication. She was allowed leave with her family and was provided with a seven day prescription for risperidone with which she had been compliant. Her psychiatrist expected that she would be discharged home within that week.

66. The deceased’s mother told the inquest that Graylands was a lifesaver for the deceased over many year

67. In these circumstances, I am satisfied that the quality of the treatment and care received by the deceased from the medical and nursing staff at Graylands was reasonable and appropriate.

B P King Coroner 11 April 2014

Romuald (Ronald) Zak (24)

Romuald (Ronald) Zak (24)