- Home Page

- INL_USANews

- INLWorldNews

- AustralianAsiaNews

- Contact Us

- WikiLeaksJulianAssange

- USPlanToDestroyWikiLeaks

- US_SetUP_JulianAssange

- AFP_WikiCommitsNoCrime

- WhatIsWikiLeaks?

- AssangeFearsMurderInUSA

- Collateral MurderVideo

- Wiki_Guardian'sUSCables

- Persson_Lindh_Murder_CIA

- Anna Lindh'sMurde_rCIA

- DomocracyNow_WikiLeaks

- CIASetUpJullianAssange

- WikiLeaksCables30Dec2010

- WikiLeaks_Mirrors

- GenocidebyNaziT4Dctors

- GodHelpAmerica&TheWorld

- RothschildOwnWarCIA_MI5

- RothschildNWOMassMurders

- RothschildMI5_CIA_Mossad

- RothschildMI5SovietAgent

- Glen_Kealy_the Sculptor

- rothschildarchives

- NoArms_NoLegs_NoWorries

- HouseOfRothschildP1

- RothschildsWorldControl

- WikiLeaksTruthAlwaysWins

- WatersWrongfulConviction

- RothschildsWorldControl1

- BernardMadoffPonziScheme

- USAStarSpangledBanner

- Elle_Magazine_Highlights

- TheInnocenseProject

- FentonTwevellian_Poems

- FrontLineJournalismClub

- CorruptLondonMetPolice

- CorruptLondonAttorneys

- ingramWinterGreen_Legal

- CorruptHighCourtJudges

- LondonJewishMafia

- AncientAmerica-TheOlmecs

- Diana-Remembered-Part3

- Diana-Remembered-Part1

- Diana-Remembered-Part2

- Diana-Remembered-Part4

- BilderbergGroupHistory1

- Diana-Remembered-Part4

- RothschildZionistPromise

- CIASetUpJullianAssange

- IlluminatiNewWorldOrder1

- IlluminatiNewWorldOrder2

- USEmbassyCablesPart1

- USEmbassyCablesPart2

- USEmbassyCablesPart3

- LinbyaGadhafiNatostrikes

- AWNWorldNews_Dec_2008_P1

- MostPowerfulFamiiesPart1

- MostPowerfulFamiliesP2

- MostPowerfulFamiliesP3

- USAsLastNail_RonPaul

- USAPresidentsPart1

- USAPresidentsPart2

- USAPresidentInaugural1

- YahooNews_5_June2011

- YahooNews_6July_2011

- YahooNews_7July_2011

- NewsofTheWorld_ClosedP1

- NewsofTheWorld_Closed_P2

- Illuminati-History-Part1

- PresidentH.W&GW_Bush

- WillTheMurdochsgetJail

- INLWorldNewsJune2008

- YahooNews_10July_2011

- Illuminati-History-Part2

- Yahoo-INLNews_11July2011

- ScotlandYardWantsMurdoch

- AlexJones_NewMan_V_HuMan

- EdinburghFringeFest_2011

- JordonMaxwellWorldViews1

- AmyWinehouse_Dionne-Last

- JamesJoyce_MollyBloom

- INLNews_2008_History

- USAWeeklyNewsHistory2005

- ShaneBauer_JoshFattal

- INLNews_History-2010_P1

- HMLandRegistryCorruption

- UKRoyalCourtsOfInJustice

- Anti_Freemason-argument

- Leveson_Media_Inquiry

- PoliceFramed_Micklebergs

- CorruptJudges_CreditLaws

- Sodahead_Public_Opinion

- Australian_Media_Shakeup

- NewsFollowup_WorldNewsP1

- WhoMurderedThomasAllwood

- INLNews_Photos_June2012

- KatieHomesTomCruiseSpilt

- GoogleLinksThomasAllwood

- MurdochsOrderMediaBlock

- INLNewsPhotos_August2012

- USAPresident2008Election

- USANews_HillaryClintonP1

- USANews_Barack_Obama_P1

- USANews_Mitt_Romney_P1

- USANews_John_McCain_P1

- Trial_KyleMontgomery2012

- ReignofEvil_MindControl

- Page 112

- ClaremontSerialMurdersP1

- LenBuckeridge&SPKoh_BGC

- ClaremontSerialKillerCSK

- CSK_websleuths.com_P1

- CSK_websleuths.com_P2

- ClaremontSerialKillings2

- ClaremontSerialKillings3

- ClaremontSerialKillings4

- DavidCaporn_MallardCase1

- PoliceRoyalCommissionWA1

- WAPoliceCSK_Incompetance

- ClaremontSerialKillings5

- ArgyleDiamonds_WA_Police

- MissingMurdered_WestAust

- WestAustralianElections

- WestAustralianElections

- WesternAustralianPrisons

- MarkMcGowan_WAPremier

- KarlO'Callaghan_WAPolice

- RomualdZakHospitalMurder

- CrimeJustice_SubiacoPost

- AmandaForrester_DPPforWA

- MafiaAustraliaMurderDrug

- MafiaTriadGangsAustralia

- AustralianCrimeBossesP1

- RogerHughCookWestAustMLA

- BrendonOConnellSpeaksOut

- BrendonOconnell_TheTruth

- WAustralianPoliceHistory

- WesternAustralianHistory

- WorldW1AustralianHistory

- TaxExemptFoundationsDodd

- Zionist_Israel_MossadWeb

- HarcourtsRE_AdamSheilds

- AdolfHitlerFactsHistory

- SexDollsAreOfTheFuture

- StrangeEvents&Creatures1

- Business_Political_News1

- PrincessDianasMI5Murder1

- YRealEstate.asia

- ClaremontSerialKillerP5

- WA_NewPoliceCommissioner

- GeneGibson_SetUpByPolice

- IlluminatiExposedHistory

- NuganHandBank_CIA_Drugs

- BannedInBritain_VideosP1

- WebOfEvil_ElmGuestHouse1

- Latest_Updated_CSK_News1

- CIA-Control-of-Australia

- CIA_Terrorism_FalseFlags

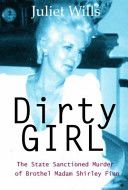

- ShirleyFinnMurderInquest

- CSK-BradleyRobertEdwards

- LionelMurphy_AbeSaffron1

- Scientology_MI6_RootsP1

- Ron_Hubbard_GroomedByMI6

- Ron_Hubbard_MI6_Agent_P2

- Scientology_createdbyMI6

- IlluminatiMKUltraFormula

- MafiaAustraliaDrugMurder

- MKUltra_HypnoticTriggers

- MKUltra_LyingDeceitSkill

- Drug_Use_In_Mind_Control

- ClaremontSerialKillings6

- Gus_McCann_Irish_Singer

- Khashoggi_Slaying_ News

- Byron_Bay_NSW_Australia

- FreddieMercury_LifeTimes

- Death-of-Fairfax-MediaP1

- DrugDealers_&Informants1

- CanadianHolocaustHistory

- HowCIACreatedBinLaden-GL

- CarlyleGroupBCCI_Arbusto

- OperationMindControl_MKU

- Sociology_of_Sex_Work_P1

- Google_Bias_Investigated

- MovieStarsWhoHatedtoKiss

- RothchildCIASorosPuppets

- Royal_Kids_All_Grown_Up

- CelebrityKids_AllGrownUp

- CelebrityKids_NowGrownUp

- MarketMentalakaRantSpace

- BabyBlackSwanStudy-ByINL

- AWN_DailyNewsFeeds_P1

- YahooAWNNewsFeedsP1

- ReutersNewsFeedsP1

- AWNNews_Back_In_Time_P1

- AWNNews_WayBackInTime_P2

- AWNNews_WayBackInTime_P3

- AWNNews_WayBackInTime_P4

- CharlesMason_JohnWGacyP1

- SaudiWomenTryingToEscape

- ClaremontSerialKillings8

- MarquessofBlayne-Harlots

- DavidJCapornCorruptionP1

- DavidJCapornCorruptionP2

- SarahAnnMcMahonInquest

- ClaremontSerialKillings9

- How_prisoners_spend_Xmas

- IrishNews20thMarch2019

- TasmanianDevils_Survival

- Top30_MostBeautifulWomen

- ARTICHOKE_Project_Olson

- BIS_BankInternSettlement

- JulianAssange_ArrestedP1

- EconomicHitMan_Confess

- JulianAssangeArrestedP2.

- JulianAssangeArrested_P3

- JulianAssange_Arrest_P4

- TriumphOfTruthBookStolen

- MI6_James_Casbolt_Speaks

- MI6_CIA_Mossad_ASIO_KGB

- Kanopy_Documentary_Films

- Assange_Snowden_Files_P1

- EdwardSnowden_AssangeP.2

- Ron_Hubbard_Scientology1

- Ron_Hubbard_Scientology2

- Bear_Faced_Massiah_LRH1

- BearFacedMessiah_LRH_P2

- Scientology_RonHubbardP5

- Mary_Sue_Hubbard_Story_1

- SecretBasesOnPlanetEarth

- Woodstock_Festival_1969

- AnnieJacobsen_USA_Author

- FailCompilation_July2016

- GreatPerthMintSwindleP1

- Corvid_19_Exposed

INLNews USAWeeklyNewsNews Easy To find Hard To Leave EdinburghFringeFest USAWeekendNews.com

GMail HotMail MyWayMail AOLMail YahooMail GMail USA MAIL ReutersNewsVideos inl.org inl.gov inl.co.nz

INLNs CNNWorld IsraelVideoNs NYTimes WashNs WorldMedia JapaNs AusNs WorldVideoNs WorldFinanceChinaDaily IndiaNs

USADaily BBC EuroNs A

AdeaideNews TasNews ABCTas DarwinN Top Stories Video/Audio Reuters AP AFP The Christian Science Monitor U.S. News & World Report AFP Features Reuters Life! NPR The Advocate Pew Daily Number Today in History Obituaries Corrections Politics LocalNews o BBC News Video Reuters Video AFP Video CNBC Video Australia 7 News Video CBC.ca Video NPR Audio Kevin Sites in the Hot Zone Video Richard Bangs Adventures Video Charlie Rose Video Expanded Books Video Assignment Earth Video ROOFTOPCOMEDY.com Video Guinness World Records Video weather.com

LionelMurphy_AbeSaffron1

100 Best Things to do in Ireland

by Jen Miller

Jen Reviews

https://www.jenreviews.com/best-things-to-do-in-ireland/

Often referred to as the “Emerald Isle”, Ireland is a place of renowned natural beauty, with a rich, diverse history that can be discovered through its many ancient castles, historic towns and sea-side villages. Expect a warm welcome from the locals - whose legendary hospitality, traditional music and famous beer make this one of the most charming islands in the world.

Contents

- 1. Cliffs of Moher (Liscannor)

- 2. The Book of Kells at Trinity College (Dublin)

- 3. Wild Atlantic Way (Galway)

- 4. The Burren (County Clare)

- 5. Guinness Storehouse (Dublin)

- 6. Glenveagh National Park (County Donegal)

- 7. The Blarney Stone at Blarney Castle & Gardens (Blarney)

- 8. Grafton Street (Dublin)

- 9. Killarney National Park (County Kerry)

- 10. Glendalough (County Wicklow)

- 11. Johnnie Fox's (Dublin)

- 12. Muckross House & Gardens (County Kerry)

- 13. Kilmainham Gaol (Dublin)

- 14. Ring of Kerry (County Kerry)

- 15. Rock of Cashel (County Tipperary)

- 16. Castletown House (County Kildare)

- 17. Brittas Bay (County Wicklow)

- 18. Portmarnock Golf Club (Dublin)

- 19. Garinish Island (Bantry Bay)

- 20. Slieve League (Carrick)

- 21. National Botanic Gardens (Dublin)

- 22. Aran Islands (Galway)

- 23. Sugarloaf Mountain (Dublin)

- 24. Bunratty Castle (County Clare)

- 25. Brú Na Bóinne (County Meath)

- 26. Shop Street (Galway)

- 27. Gap of Dunloe (Killarney)

- 28. St Patrick's Cathedral (Dublin)

- 29. Drombeg Stone Circle (County Cork)

- 30. Knocknarea Mountain (County Sligo)

- 31. Dun Aonghasa (Inishmore)

- 32. King John's Castle (Limerick)

- 33. Charles Fort (Cork)

- 34. Newgrange (County Meath)

- 35. O’Donoghue’s Bar (Dublin)

- 36. National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology (Dublin)

- 37. Dunbrody Abbey (County Wexford)

- 38. Copper Coast Geopark (County Waterford)

- 39. Eask Tower (County Kerry)

- 40. Spike Island (County Cork)

- 41. Dublin Castle (Dublin)

- 42. The Dingle Peninsula (County Kerry)

- 43. The English Market (Cork)

- 44. The Little Museum of Dublin (Dublin)

- 45. Mount Usher Gardens (County Wicklow)

- 46. Galway Cathedral (Galway)

- 47. Kells Priory (County Kilkenny)

- 48. Fota Wildlife Park (County Cork)

- 49. Gallarus Oratory (County Kerry)

- 50. Ardmore (County Waterford)

- 51. Atlantic Drive on Achill Island (Westport)

- 52. Sky Road (Clifden)

- 53. Ailladie (County Clare)

- 54. Dunmore Cave (County Kilkenny)

- 55. Barryscourt Castle (County Cork)

- 56. Dingle Harbour (County Kerry)

- 57. Ballyhoura Mountains (Limerick)

- 58. Uragh Stone Circle (County Kerry)

- 59. Phoenix Park and Dublin Zoo (Dublin)

- 60. Dingle Distillery (County Kerry)

- 61. Valentia Island (County Kerry)

- 62. Carrowmore (County Sligo)

- 63. Coral Beach (Galway)

- 64. Cooley Peninsula (County Louth)

- 65. Dingle Peninsula (County Kerry)

- 66. Zipit Tibradden Wood (Dublin)

- 67. Mizen Head (County Cork)

- 68. Donegal County Museum (County Donegal)

- 69. Dublin Writers Museum (Dublin)

- 70. County Carlow Military Museum (Carlow)

- 71. Cratloe Woods (County Clare)

- 72. Malahide Castle & Gardens (Dublin)

- 73. Dunguaire Castle (Galway)

- 74. Cork City Gaol (Cork)

- 75. Lough Gur (County Limerick)

- 76. Jerpoint Abbey (County Kilkenny)

- 77. Cobh Heritage Centre (County Cork)

- 78. Clara Bog (County Offaly)

- 79. The Rock of Dunamase (County Laois)

- 80. The Donkey Sanctuary (County Cork)

- 81. Powerscourt Estate (County Wicklow)

- 82. Áras an Uachtaráin (Dublin)

- 83. Saltee Islands (County Wexford)

- 84. Emo Court (County Laois)

- 85. The Brazen Head (Dublin)

- 86. Night Kayaking (County Cork)

- 87. Dunsany Castle (County Meath)

- 88. Burrishoole Abbey (County Mayo)

- 89. Creevykeel Court Cairn (Sligo)

- 90. Glasnevin Cemetery (Dublin)

- 91. Old Jameson Distillery (Dublin)

- 92. Kilmurvey Beach (County Galway)

- 93. Blennerville Windmill (County Kerry)

- 94. St. Michan's Church (Dublin)

- 95. Moneygall Village (County Offaly)

- 96. Knockma Woods (County Galway)

- 97. The Irish Sky Garden (County Cork)

- 98. The Hole of the Sorrows (County Clare)

- 99. Lambay Island (Dublin)

- 100. Burkes Beach Riding (Killarney)

1. Cliffs of Moher (Liscannor)

With over 1 million visitors a year, the spectacular Cliffs of Moher are one of Ireland’s most famous natural beauties - rising dramatically to 120m above the Atlantic Ocean. On a clear day, visitors are rewarded with stunning views as far as the Aran Islands in Galway Bay and the Maum Turk Mountains in Connemara.

Wildlife is abundant here and you can find Ireland’s only mainland breeding colony of Atlantic Puffins. Take a 1-hour cruise to see these incredible birds up close, along with Razorbills, Kittiwakes and Choughs.

2. The Book of Kells at Trinity College (Dublin)

Ireland’s most prized national treasure, The Book of Kells is a beautifully illustrated gospel book containing four of the New Testament gospels in Latin. Dating back to around 800 AD, The Book of Kells can be seen on display in the grand Old Library of Trinity College, in the heart of Dublin.

Take the official 30-minute tour to learn about the fascinating five hundred year history of the building, delivered by students of the college.

3. Wild Atlantic Way (Galway)

Wild rugged seascapes, winding cliff-side roads, ancient castles and fairy lore - Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way epitomises the spirit of the Emerald Isle whether you drive, cycle or hike its 2,500km of coastal road. As the longest defined coastal touring route in the world, the Wild Atlantic Way stretches from Londonderry Derry in the north, all the way to Kinsale in the south, with many different itineraries to choose from. Plan your own epic route, or follow one of the three or four-day guides from the official website.

4. The Burren (County Clare)

One of Ireland’s six national parks and encompassing around 250 square kilometres, The Burren in County Clare is home to spectacular rock formations, cliffs, caves and fascinating archeological sites - with over 2500 recorded monuments. Book a one-day hiking tour of the park’s most famous peak - Mullaghmore Mountain - to discover the unique flora and fauna native to The Burren.

5. Guinness Storehouse (Dublin)

Discover the history behind Ireland’s most famous beer - Guinness - at the St. James’s Gate Brewery in the heart of Dublin. From the life of founder Arthur Guinness to the ingredients that make a pint of the “black stuff” popular all over the world, a trip to the Storehouse is an essential part of a trip to the capital city. Skip the queues by joining a 75-minute connoisseur tasting session, which ends in the famous 7th floor Gravity Bar - where you can enjoy 360 degree views of Dublin.

6. Glenveagh National Park (County Donegal)

Centred around the impressive 19th century Glenveagh Castle, the Glenveagh National Park is the second largest in the country, stretching over 16,000 acres. With a wealth of wildlife - including red deer - the park’s many walks, hikes and gardens showcase natural Ireland at its very best. Be sure to bring along a good hiking backpack!

Book a 30 minute castle tour to hear the history of the house and the exotic walled gardens in the grounds.

7. The Blarney Stone at Blarney Castle & Gardens (Blarney)

Visit Blarney Castle and kiss the famous Blarney Stone, which is said to give those - who brave the slight vertigo-inducing position required in order to place your lips upon it - the gift of eloquence, or as they say in Ireland, the “gift of the gab”.

Opinion varies on the exact story behind the myth of the stone - with some saying that it was a gift to the Irish from Scotland in return for sending men to help King Robert the Bruce defeat the English during the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, while others claim it was brought back to Ireland during the Crusades. Whatever the history behind the legend, famous faces from all over the world have made the journey to kiss the stone - including Winston Churchill and Mick Jagger.

Book a one day tour to discover the fascinating history behind the castle, gardens and the stone.

8. Grafton Street (Dublin)

Indulge in a little sightseeing and shopping on Dublin’s most famous street. Grafton Street not only features world-famous shops but also historical building and beautiful architecture. Now a popular spot for street performers, musicians and entertainers, examples of Grafton Street’s traditional businesses can still be found in between the high street names - including the famous Bewley’s Grafton Street Café.

Pick up a free Dublin Street map from the tourist office on Grafton Street, where the friendly staff offer advice and tips on the best hidden destinations.

9. Killarney National Park (County Kerry)

Rugged mountains that sweep to sparkling lakes, woodlands packed with an abundance of wildlife and hiking trails which lead to hidden waterfalls - Killarney National Park is an area of outstanding natural beauty. Featuring the highest mountain rage in Ireland - McGillycuddy's Reeks - and the 15th Ross Castle, the National Park is best explored by foot. The Muckross Lake Loop, which includes the impressive Torc waterfall, takes roughly 3 - 5 hours following the official trail.

10. Glendalough (County Wicklow)

Stunning scenery and fascinating history awaits at Glendalough - one of Ireland’s most beautiful locations. Home to the Monastic Site with Round Tower, the “Valley of the Two Lakes” has several challenging walks and trails for the more adventurous traveller. Join a 6-day guided walking tour to experience everything this incredible area has to offer.

11. Johnnie Fox's (Dublin)

Experience a true Irish pub atmosphere at Johnnie Fox's, one of the oldest pubs in Ireland. Established in 1798, the pub is famous for its traditional music sessions, storytellers, house bands, dancers and award-winning seafood kitchen. The pub is only about 30 minutes away from Dublin city centre.

12. Muckross House & Gardens (County Kerry)

The 19th century Muckross House stands on the banks of the beautiful Muckross Lake, Killarney. Visited by Queen Victoria in 1861, the house and its surrounding gardens are exceptionally well kept, but it’s the traditional farms dotted around the estate that make this a truly unique experience - transporting visitors back to rural Ireland in the 1930’s and 40’s. Take a tour of the house and then follow the map of the traditional farms to experience life in the early 20th century.

13. Kilmainham Gaol (Dublin)

Now a busy museum, the former prison of Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin offers a fascinating look at the history of some of Ireland’s most famous revolutionaries - including the leaders of the Easter Risings. Book a 90-minute guided tour in advance to beat the crowds and experience what life was like behind bars for the prisoners held, and later executed, here.

14. Ring of Kerry (County Kerry)

The Iveragh Peninsula - more commonly referred to as the Ring of Kerry - is a tourist trail in County Kerry that features some of the finest driving scenery in Ireland, incredible beaches and ancient monuments. Visitors can also experience the breathtaking views by canoe or kayak - joining one of the exciting water day tours that set off from Killarney.

15. Rock of Cashel (County Tipperary)

Holding one of the finest collections of Celtic art in Europe, the historic site at the Rock of Cashel was the former seat of the old kings of Munster - whose ancestors later handed the main fortress over to the church. There are several ancient buildings to explore, including the Romanesque chapel - said to be the best example in Ireland. Book ahead to guarantee a place on one of the 45-minute tours, ending with the stunning view of Tipperary from the rock.

16. Castletown House (County Kildare)

The largest and most impressive example of Palladian-style houses in Ireland, Castletown was once the home of the Speaker of the Irish House of Commons. The famous palace-like building was carefully restored and opened to the public in 1967, showcasing exquisite furniture, decor and artworks from the previous owners. Join one of the free 45-minute tours to learn about the history of the house and the families that once lived here.

17. Brittas Bay (County Wicklow)

Considered the finest beach on Ireland’s east coast, Brittas Bay in County Wicklow is a gorgeous 2 mile stretch of powdery sand, backed by large sand dunes. Home to an array of wildlife, the beach and dunes are a favourite of nearby Dubliners during the summer months. Surfers can enjoy the Irish Sea waves, or beginners can take a morning surf lesson with the local training school.

18. Portmarnock Golf Club (Dublin)

Considered the best golf course in Ireland, and often included in round-ups of the best courses in the world, Portmarnock Golf Club has a stunning scenically setting on the east coast, just 10 miles north of Dublin.

Try your hand on the link’s 27 holes - including the famous 15th hole - before relaxing in the historic club house.

19. Garinish Island (Bantry Bay)

Explore the beautiful gardens of Garnish (or Garinish) Island in Glengarriff Harbour, Bantry Bay. Take the 30-minute ferry from Glengarriff Pier and walk amongst the unusual plants to discover what makes these picturesque gardens world famous. Don’t forget to visit the Martello tower on the south of the island for a breathtaking view over Bantry Bay.

20. Slieve League (Carrick)

Three times higher than the peaks of the Cliffs of Moher, the mountain of Slieve League in County Donegal offers incredible walks and views - including the famous "One Man's Path" track. Take a one-day “Highlander Tour” to experience the outstanding beauty of this area with a safe and trained guide.

21. National Botanic Gardens (Dublin)

One of Dublin’s most popular free attractions, the beautiful Botanic Gardens are a place of peace and tranquility, set in a spectacular glass building. Home to over 20,000 types of living plants, with many more dried specimens, the garden is a horticulturalist dream. Download one of the free audio tours as your companion while you wander amongst the rare plants.

22. Aran Islands (Galway)

The three islands of Inis Mor, Inis Meain and Inis Oirr make up the Wild Atlantic Way’s spectacular Aran Islands - one of Ireland’s most unspoiled destinations. Similar to the landscape of the Burren, the limestone islands offer endless activities for adventure seekers but the best way to explore is by bike. Rent a mountain bike and cycle the 1 hour loop to the prehistoric hill fort of Dun Aonghasa.

23. Sugarloaf Mountain (Dublin)

Dominating the skyline, the Sugarloaf Mountain was once used as a milepost for pilgrims making their way to the monastery at Glendalough. In present times, the mountain is a popular hiking spot, with an easy 1-hour hike to the top, providing stunning views of the surrounding landscape.

24. Bunratty Castle (County Clare)

Travel back in time to the 15th and 19th centuries at Bunratty Castle and Folk Park - Ireland’s most authentic medieval castle. Take a stroll around the charming village in the park, wander the colourful gardens or join one of the daily tours of the castle to find out more about the lives of the people who lived and worked here.

25. Brú Na Bóinne (County Meath)

One of the world’s most important historic sites, Brú na Bóinne contains three passage tombs - Knowth, Newgrange and Dowth. In addition to the tombs, almost 100 other monuments have been recorded in the area, as well as some of the finest examples of megalithic art in Europe. Jump on a day-tour from Dublin to see the best of Newgrange and Knowth, and discover the Hill of Tara and the exhibitions of the visitor centre too.

26. Shop Street (Galway)

Galway’s main shopping street is packed full of stores, pubs and high-street names, housed in a range of historic buildings including Lynch’s Castle - now a branch of the Allied Irish Banks. More of a townhouse than a traditional castle, the building still features an interesting and somewhat grim history - being the spot where the Lord Mayor had his own son hung for violating the law. Join one of the 90-minute walking city tours to discover the secrets of this old-world street.

27. Gap of Dunloe (Killarney)

Explore the stunning scenery of the narrow mountain pass of Dunloe in Killarney. This has been one of the most popular visitor spots in Ireland for decades, and with the option to see the gap by horse-drawn carriage, boat or horseback, you’ll feel like you’ve stepped back in time. Book a four-hour boat and pony tour to see the best of the lakes and the gap.

28. St Patrick's Cathedral (Dublin)

The National Cathedral of Ireland, St Patrick’s in Dublin has been a holy site for over 1500 years. Gulliver’s Travels author Jonathan Swift, who was Dean of the Cathedral in the 1700’s, is buried here – alongside notable churchmen and soldiers. Join one of the 2.5 hour guided tours of the Cathedral to learn about the history of Ireland’s most famous Saint and the building that bears his name.

29. Drombeg Stone Circle (County Cork)

Just east of Glandore in County Cork, the Drombeg Stone Circle is the most famous megalithic site in Ireland. Known by the locals as the “Druid's Altar”, 17 of the recumbent stones survive - reaching up to 2-metres high. Learn the history of the pagan rituals and how the stone age people survived on a one day tour of County Cork.

30. Knocknarea Mountain (County Sligo)

County Sligo’s striking mountain offers excellent hiking and, although not confirmed through excavation, is believed to hold the Neolithic passage tomb of Queen Maeve of Connacht within its mound, thought to date back to around 3000 BC. The one-hour hike to the top is steep, but rewards climbers with wonderful views of the the Ox Mountains.

31. Dun Aonghasa (Inishmore)

One of several ancient hill forts on the Aran Islands in County Galway, Dun Aonghasa is generally considered to be an excellent example of barbaric monuments in Europe. Perched on the cliff edge of Inishmore, the site also offers spectacular views of the entire island. Hop on a one day Aran Bus tour to see the best of this 14 acre site.

32. King John's Castle (Limerick)

Situated on the “King’s Island” on the River Shannon in Limerick, King John’s Castle has over 800 years of fascinating history to discover. After a multi-million euro investment was completed in 2013, the castle now features interactive activities and exhibitions - including a blacksmith's forge and a medieval campaign tent in the courtyard. Book your admission ticket in advance to spend a day exploring Ireland’s most famous castle.

33. Charles Fort (Cork)

Over 300 years old, the star-shaped Charles Fort is associated with some of the most important moments in Ireland’s history, including the Irish Civil War and the Williamite War. Created during the reign of King Charles II, the fort occupies more than 20 acres and is best seen as part of a one day tour of Cork.

34. Newgrange (County Meath)

Considered the “Jewel of Ireland’s ancient East”, Newgrange is a world-famous 5200 year-old passage tomb in County Meath, north of Dublin. A World Heritage Site, Newgrange reaches

85m in diameter and 13.5m in height and is surrounded by 97 kerbstones - some of which feature incredibly well-preserved examples of megalithic engravings. Visit the The Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre to secure a place on one of the 2-hour guided toursthat leave at regular intervals.

35. O’Donoghue’s Bar (Dublin)

Famous for being the starting point for popular Irish band The Dubliners, O’Donoghue’s Bar has a long and closely-connecting history with traditional Irish music. Well known faces of those who have played the venue cover the walls and the bar is still one of the best places to catch live sessions in the city. Visit at 9pm on weekdays or 5pm on a Saturday to hear the next big thing in Irish music.

36. National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology (Dublin)

Covering Ireland’s varied and fascinating history from the Stone to Middle Ages, the National Museum of Ireland has a range of permanent and visiting exhibitions - from ancient Irish artefacts to Bronze Age gold. The museum takes roughly one hour to visit and is best seen by following the official downloadable floorplan.

37. Dunbrody Abbey (County Wexford)

At 59m, Dunbrody Abbey is one of the longest churches in Ireland, having been built in the 13th century. It is also one of the only churches to feature a full-sized hedge maze - featuring over 1500 yew trees and pebble paths. A one-hour guided tour of the Abbey and the maze can be booked in advance or visitors are given a self-guide sheet on arrival.

38. Copper Coast Geopark (County Waterford)

Declared a European Geopark in 2001 and a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2004, Ireland’s Copper Coast is an area of outstanding natural beauty - with secret beaches and hidden coves stretching over Ireland’s southern coast in County Waterford. Request a self-tour map of the coastal route or download one of the walking trail cards to experience the best of the region.

39. Eask Tower (County Kerry)

Built in the 1840’s to guide ships into Dingle Harbour, Eask Tower is made of solid stone and sits on top of Carhoo Hill - where it stands at 600 ft above sea level. The tower was later used as a look-out post during World War II. Start from Dingle and walk the 8-mile return route for incredible views from the top.

40. Spike Island (County Cork)

Home to Fort Mitchell - a star-shaped military fort dating back to the 18th century - Spike Island lies within Cork Harbour and covers 103 acres. Used as both a defence location, as well as a prison, Spike Island was originally home to an early monastic settlement. Take the short scenic ferry from Kennedy Pier in Cobh and spend two hours touring the island.

41. Dublin Castle (Dublin)

With a complex history dating back to as early as 930, Dublin Castle has long been the centre point of the city. It was the Vikings who originally built a fortification here - taken over by the Normans during the invasion, although it was the English who built the first elements of a traditional castle. Wander around the grounds for free or book a paid-for two-hour guided tour of the State Apartments and Chapel Royal.

42. The Dingle Peninsula (County Kerry)

Stretching for over 30 miles, the Dingle Peninsula is home to a range of outdoor activities and stunning coastal scenery. Explore Mount Brandon - Ireland’s second highest mountain - and take in the view of the uninhabited Blasket Islands to the West. Take a one hour boat tour to meet area’s most popular resident - Fungie the Dingle Dolphin.

43. The English Market (Cork)

Considered one of the best covered markets in Europe, and visited by Queen Elizabeth during her 2011 State trip, the English Market in the centre of Cork has become an increasingly popular tourist destination. Built in the mid-19th century, the market is now a multicultural hub for foodies, but is still most famous for its traditional butchers and fishmongers.

44. The Little Museum of Dublin (Dublin)

Join one of the popular 30 minute tours of Dublin’s newest and most compact museum - The Little Museum of Dublin. Featuring a collection created entirely by public donation, the museum offers an intriguing look into life in the capital over the past 100 years.

45. Mount Usher Gardens (County Wicklow)

An excellent example of Robinsonian-style garden design, Mount Usher is home to one of Ireland’s finest collections of trees, shrubs and flowers. A 90-minute tour by one of the garden’s expert guides is the best way to discover the unmissable sights during each different season.

46. Galway Cathedral (Galway)

The newest of the great cathedrals of Europe, The Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St Nicholas - most commonly referred to as simply Galway Cathedral - is the largest building in the city. Constructed on the site of an old prison, the Cathedral is now a popular tourist destination and visitors can join one of the all-day hop-on, hop-off historic tours to view this and many more of Galway’s top sites.

47. Kells Priory (County Kilkenny)

The impressive Kells Priory is one of the biggest and best examples of medieval structures in Ireland. Founded in 1193, the Priory has suffered much over the years - including fires that destroyed much of the original buildings on three different occasions. Book an afternoon tour to climb the tower - be warned, the stairs are not for the faint of heart!

48. Fota Wildlife Park (County Cork)

Spread over 100 acres, just outside of the city of Cork, Fota Wildlife Park is the second most popular attraction in Ireland - drawing just under 500,000 visitors each year. From the most recent additions to the Fota family - Asian lions - to the many other breeds of animals and plants, the wildlife park is the perfect day trips for families. Download the Fota Wildlife Park Map for free before you visit or for a more hands-on experience, join a behind the scenes day-trip.

49. Gallarus Oratory (County Kerry)

Still in near perfect condition, the stone, upside-down boat structure of Gallarus Oratory was a place of early Christian worship by local farmers and is believed to have been built sometime around the 6th century. It’s status as a holy place is known throughout the world. Book a place on the popular Archaeological Day Tour to see this and other nearby monuments.

50. Ardmore (County Waterford)

The picturesque seaside town of Ardmore in County Waterford is the perfect place to indulge in outdoor activities. Take a hike along the cliffs, learn to surf on beautiful Ballyquin Beach or try out a stand up paddle board at the activity centre.

51. Atlantic Drive on Achill Island (Westport)

Stretching for approximately 80 miles of the County Mayo coastline, the Atlantic Drive is a stunning route, best seen by car or bike but the area also offers a fantastic range of water activities - including scuba diving. Learn to dive in one day with a Discover Scuba course

52. Sky Road (Clifden)

Winding up amongst the hills of Clifden Bay, the Sky Road is famous for its jaw-dropping views of the sea and the islands of Turbot and Inishturk. Cycling the 17km loop from Clifden is one of the best ways to experience all that this fascinating region has to offer.

53. Ailladie (County Clare)

One of the most popular rock climbing locations in Ireland, Ailladie on the coast of The Burren in County Clare has roughly 170 climb routes - ranging from 8m to 30m. The climbing is considered relatively difficult but learners can start with a Climbing Hidden Tour.

54. Dunmore Cave (County Kilkenny)

Known as the spot of a viking massacre in 928 A.D, Dunmore Cave is a fascinating series of underground chambers where visitors can discover the finest calcite formations in all of Ireland. Spend one-hour exploring this world beneath the ground.

55. Barryscourt Castle (County Cork)

The 14th century Barryscourt Castle is an excellent example of a traditional Irish tower house and is one of the most popular visitor spots in County Cork. Explore the beautiful Tower House Gardens - designed and laid out as they would have originally been. Join one of the free hourly tours to learn about the history of the historic Barry family home.

56. Dingle Harbour (County Kerry)

The charming Dingle Harbour is the perfect place to explore the surrounding coastline and history of the town - having once been a major port during the late 13th century. These days, boat trips depart daily and you can discover the local history on one of the day tours that leave at regular intervals from the harbour.

57. Ballyhoura Mountains (Limerick)

Crossing both the borders of County Cork and County Limerick, the Ballyhoura Mountains offer thrill-seekers some of the best mountain bike trails in the entire country. There are just under 100km of trails to discover, from easy 6km routes to 50km Castlepook loop.

58. Uragh Stone Circle (County Kerry)

Smaller in size than some of Ireland’s other megalithic monuments but positioned beautifully overlooking Lough Cloonee Upper and Lough Inchiquin, the stone circle at Uragh is part of the stunning Gleninchaquin Park. There are many spectacular walks and hikes within the park, including the short mapped trek to the Stones.

59. Phoenix Park and Dublin Zoo (Dublin)

One of the most popular tourist sites in Dublin, Phoenix Park and Dublin Zoo make for an amazing day out for all the family. With an array of wild animals and a focus on learning, visitors to the zoo can book a private guided day tour to discover everything that happens behind the scenes.

60. Dingle Distillery (County Kerry)

Producing unique, artisan whiskey, vodka and gin, the Dingle Distillery has been offering customers independent distilling since 2012. Get a behind the scenes look at how the distillery works on a one-hour tour - where you’ll also be invited to taste some of the drinks.

61. Valentia Island (County Kerry)

At only 7 miles long by 2 miles wide, Valentia is a small island and one of the most westernly points in Ireland. With just 600 inhabitants, it’s a charming and peaceful place to explore - especially by bike. Hire one for the day from Kerry, cycle over the bridge and be rewarded with breathtaking views.

62. Carrowmore (County Sligo)

As one of the four main passage tombs in Ireland, the Carrowmore Megalithic Complex is a popular spot for tourists visiting County Sligo. Join a seven-day tour of Ireland’s most ancient mystical locations to see the tomb and many of the other surrounding sites.

63. Coral Beach (Galway)

Famous for its fine coral, the Blue Flag 2014 Coral Beach is a place of unspoilt natural beauty on the Galway coast, near the village of Carraroe. Perfect for swimming and snorkelling, it is also possible to charter a yacht for the day to explore the local coastline.

64. Cooley Peninsula (County Louth)

A hilly green peninsula in County Louth, the Cooley area is known for its excellent range of outdoor activities - from horse riding through lush glens to hiking amongst ancient Irish monuments. Make like the locals and spend an afternoon with a fishing rod on the calm waters of Carlingford Lough.

65. Dingle Peninsula (County Kerry)

An outdoor lover’s paradise, the Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry ends just beyond the town of Dingle and is thought to be the most westernly point in, not just Ireland, but Europe. Explore the Cú Chulainn trail by horseback on a 1.5 hour trek and be rewarded with stunning views.

66. Zipit Tibradden Wood (Dublin)

Located in Dublin’s Tibradden Wood, Ireland’s second Zipit course allows visitors to swing through the trees and offers incredible views of the city beyond. Enjoy an afternoon spent exploring one of several different routes within the forest, or for those who prefer to keep their feet on the ground, the wood has many enchanting walks.

67. Mizen Head (County Cork)

One of the most popular points on the Wild Atlantic Way, the iconic bridge at Mizen Head allows visitors to cross the gorge below and spot wildlife including seals, whales and dolphins. Follow the route on the Wild Atlantic Way map and visit the old signal station to get a glimpse into the solitary life of the lighthouse keepers of old.

68. Donegal County Museum (County Donegal)

Located in an architecturally beautiful building, the Donegal County Museum was once part of a workhouse, but now showcases a wide collection of artefacts from County Donegal through the ages - particularly from World War I. Book a place on a two-hour bus tour of Donegal to see the Museum and the town’s other places of note.

69. Dublin Writers Museum (Dublin)

Showcasing the works of some of Ireland’s most well known and loved writers, the Dublin Writers Museum can be found in a stunning 18th century mansion. From Yeats to Wilde and Joyce - every important name in Irish literature is here. Time your visit to coincide with the lunchtime theatre and reading events.

70. County Carlow Military Museum (Carlow)

Beginning with a small memorial after the death of a soldier in the town, the County Carlow Military Museum now holds a large collection of military memorabilia - including a large portion of objects handed over by the Irish Defence Forces. Free short tours run regularly and offer insight and personal stories on Carlow’s past.

71. Cratloe Woods (County Clare)

Believed to be the origin of the wooden roof beams found in Westminster Hall, Cratloe Woods are a lovely State-owned forest next to the small village of Cratloe. Follow the one-hour trail loop to see enchanting trees, birds and more.

72. Malahide Castle & Gardens (Dublin)

The beautiful walled gardens of Malahide alone are reason enough to visit the castle - containing over 5000 different species plants. Inside, discover the history of the Talbot family, dating back to as early as 1175, through one of the expert 45-minute tours of the castle.

73. Dunguaire Castle (Galway)

A simple but beautifully positioned structure, on the edge of the water in Galway Bay, the 16th century Dunguaire Castle has been restored to give visitors an idea of what life would have looked like in olden times. For a special treat, book a place at one of the special banquet meals that run from April to October - where you can enjoy live entertainment and local produce.

74. Cork City Gaol (Cork)

If you want to get a real feel for what life was like for Irish prisoners at the beginning of last century, take a trip to the imposing Cork City Gaol. You can wander down the halls and explore the former cells throughout the day, or for those who like a scare, book a private one-hour evening tour to meet the ghosts of the Gaol.

75. Lough Gur (County Limerick)

The horseshoe-shaped lake of Lough Gur has played a crucial role in the lives of the Irish who have lived near its banks for thousands of years. Over 6000 years of archaeology and history have been discovered here and with many walking routes to choose from, join one of the expert-guided walking tours which set off at 11am on Sundays.

76. Jerpoint Abbey (County Kilkenny)

Declared a National Monument, the 12th century, Cistercian, Jerpoint Abbey is a fine example of Romanesque ruins. Guided afternoon tours are by advance booking only but include a fascinating look at the history of the church and the surrounding Jerpoint Town ruins.

77. Cobh Heritage Centre (County Cork)

Located in a beautifully restored Victorian railway station building, the Cobh Heritage Centre gives an insightful look into the lives of the Irish immigrants who travelled by sea to reach faraway lands and start new lives abroad. Visitors can also trace their own family history during their trip to find out if they have Irish roots.

78. Clara Bog (County Offaly)

Clara Bog is one of the largest raised bogs in Ireland and one of the best examples or remaining bogs in Europe. The area is home to many wild animals and birds, which can be seen on one of the private guided tours of the bog or discovered at the Clara Bog Visitor Centre.

79. The Rock of Dunamase (County Laois)

Offering spectacular views of the surrounding countryside, the Rock of Dunamase is an imposing rocky outcrop that has played an important role in the history of the County Laois area for hundreds of years. It’s an easy hike from the car park to the Rock, follow the information board at the bottom of the hill.

80. The Donkey Sanctuary (County Cork)

Animal lovers can spend the day visiting, learning and helping out with the donkeys that stay at Cork’s Donkey Sanctuary and throughout the country in the sanctuary’s rehoming program. It’s free to visit and walk around the sanctuary, or alternatively, you can adopt a donkey during your trip.

81. Powerscourt Estate (County Wicklow)

Voted National Geographic’s No.3 Garden in the World, Powerscourt Estate in County Wicklow stretched for over 43 acres and includes the beautiful Powerscourt Waterfall. A short 6km drive from the entrance to the Estate, the waterfall is Ireland’s highest at 121m.

82. Áras an Uachtaráin (Dublin)

The official residence of the President, Áras an Uachtaráin is also used as a venue for State occasions and has welcomed people including the Obamas and Nelson Mandela in the past. Visitors can purchase tickets for a one hour tour of the main reception rooms, based on a first come first served basis.

83. Saltee Islands (County Wexford)

The two islands of Great Saltee and Little Saltee lie off the picturesque coast of County Wexford and, although uninhabited by humans, are a popular breeding area for many birds. Visitors can take a one-hour boat trip to the island, where they can spot puffins, fulmars and more.

84. Emo Court (County Laois)

A neo-classical mansion with beautiful 18th century gardens, Emo Court in County Laois has become a popular tourist spot, with excellent woodland walks. Follow the 4.95 km Slí na Slainte loop walk to see some ancient trees.

85. The Brazen Head (Dublin)

Officially Ireland’s oldest pub, The Brazen Head in Dublin has been serving punters since 1198. To experience the full history and atmosphere of the pub, book a spot at an “Evening of Food, Folklore and Fairies” - a 2 hours and 45 minute night of entertainment, food and storytelling.

86. Night Kayaking (County Cork)

Experience the magic of night kayaking in County Cork with a 2.5 hour Starlight Moonlight tour on Lough Hyne. Watch the stars, spot native birds and gaze at the reflection of the moon and stars in the water as you paddle.

87. Dunsany Castle (County Meath)

The ancestral home of the Lords of Dunsany - and with the family still living there - Dunsany Castle in County Meath is a wonderful collection of paintings and furniture from the 18th and 19th centuries. Join one of the three-hour walks of the house and the garden to hear about Lord Dunsany and the history of this fine home.

88. Burrishoole Abbey (County Mayo)

Also known as Burrishoole Friary, the ruins of the abbey and surrounding cemetery are situated on the edge of a peaceful tidal estuary near Newport in County Mayo. Cycle or walk the easy “Abbey Trail” for beautiful views of the Abbey and the surrounding countryside.

89. Creevykeel Court Cairn (Sligo)

An excellent example of an Irish Court Tomb, the Creevykeel Cairn dates back to neolithic times and excavations have discovered four different burials within its stones. Drive the short 1.5 - 2 km past Cliffony and follow the signs to the carpark.

90. Glasnevin Cemetery (Dublin)

Holding over 1.5 million graves, Glasnevin is a huge cemetery that offers a unique, and sometimes sombre, look at the changing trends in grave memorials over the last 200 years. Join a 1.5 hour tour of the graves to discover the names and stories behind some of the cemetery’s most visited graves.

91. Old Jameson Distillery (Dublin)

Now a visitor attraction, the Old Jameson Distillery is the original site where Jameson Irish Whiskey was distilled until 197. To get a behind the scenes look at the process, and try a tipple or two yourself, join a guided tour of the distillery, lasting one hour.

92. Kilmurvey Beach (County Galway)

With the type of white sand and blue waters you would expect to find somewhere in the Mediterranean, rather than Ireland, the Blue Flag Kilmurvey Beach is a popular spot on the Aran Islands. Follow the “Ring of Aran” three-hour walking trail to see the beach and panoramic views of the sea.

93. Blennerville Windmill (County Kerry)

Tralee Bay’s most iconic structure, Blennerville Windmill was a main emigration point during the Great Famine. Located within the beautiful Tralee Bay Nature Reserve, hop on-board one of the Guided Nature Boat Tours to see birds, frogs and wetland mammals.

94. St. Michan's Church (Dublin)

Situated on Church Street within the city centre of Dublin, St. Michan’s Church is famous for the underground vaults, where visitors can see the mummified remains of some of Dublin’s most influential and well known families from the past three centuries. Join the Dublin Gravedigger Ghost Tour to find out more about the Church and it’s mummies.

95. Moneygall Village (County Offaly)

The small, picturesque village of Moneygall in County Offaly became famous in 2011, when American President Barack Obama visited to trace his Irish ancestral routes. Follow in the President’s footsteps and visit the The Ancestral Home and see where the Kearney Family lived before emigrating to America.

96. Knockma Woods (County Galway)

Follow the enchanting and mystical Fairy Walk through Knockma Woods, where the easy circular loop will bring you to the supposed spot of the Fairy Fortress. Look out for fairy houses and other (human-made) souvenirs amongst the trail.

97. The Irish Sky Garden (County Cork)

The strange Irish Sky Garden - designed by artist James Turrell - sits within the 163 acres of grounds at the Liss Ard Estate in County Cork. Book an overnight stay at the charming Liss Ard Hotel to see the Sky Garden for free or pay the small entry fee as a non-resident.

98. The Hole of the Sorrows (County Clare)

Often referred to as the “Hole of the Sorrows” but actually named Poulnabrone Dolmen, this neolithic portal tomb is a popular stop in County Clare. Once you’ve visited the tomb, follow the 1.5 hour Carran Turlough Loop to see more of this area of natural beauty.

99. Lambay Island (Dublin)

Ireland’s largest East Coast island is home to a rather unexpected animal - wallabies. The furry animals are thought to have been introduced on the private island by a former owner, and you can book one of the day boat trips from Skerries to see them up close.

100. Burkes Beach Riding (Killarney)

Experience the beauty of Rossbeigh Beach in Killarney, County Kerry, by horseback. Join a two-hour trek through the Curra Mountain before hitting the sand of Rossbeigh for an unforgettable afternoon’s ride.

Just

how close was the former high court judge Lionel Murphy

to the notorious crime

boss of Kings Cross Abe Saffron?

‘Murphy was his main man’: the alleged links between the judge and the crime boss Abe Safron

Untangling the relationship between Lionel Murphy and Abe Saffron baffled authorities

whose inquiries spanned NSW politics, sex trafficking and Sydney landmarks

"People got killed for what they might know," he said.

"Money was first raised from gambling, then prostitution and then drugs.

I watched it happen.

You either went along with it or got out.

"The Cross changed when the police took over the drug scene ... the police became the gangsters.

NSW premier Robert Askin was the godfather and corruption reigned supreme from the dustman to the premier."

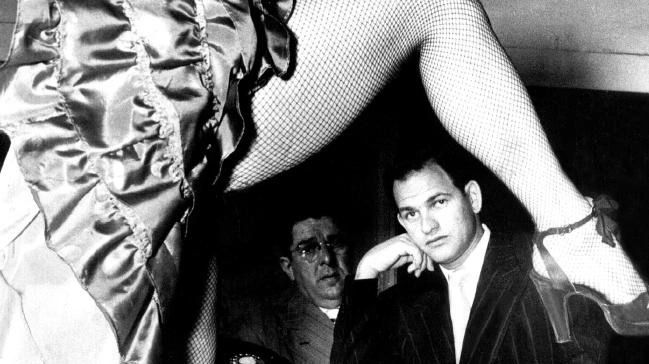

From the 1960s to the '80s, Abe Saffron was a leading player in Sydney's entertainment industry. He opened Australia's first strip joint in the Cross and brought out stars such as Frank Sinatra, Lenny Bruce, Tina Turner and Donovan. As the Vietnam War cranked up and US servicemen flooded the Cross on leave, topless go-go girls overtook the strip shows. The Americans brought money, Mandrax, marijuana and heroin. By then Saffron was wealthy; he owned hotels, motels and six clubs, including the Pink Pussycat, the Pink Panther and Les Girls (later the Carousel, where anti-development newspaper owner Juanita Nielsen was last seen alive).

In 1969, Abe Saffron installed Scottish hard man Jim Anderson as his licensee at the notorious Venus Room.

It was there that Anderson shot dead Donny "the Glove" Smith in front of off-duty NSW detectives. The case was no-billed. Ten years later, Anderson turned against him and his evidence to the National Crime Authority led to Saffron being jailed for 17 months for tax evasion.

If Abe Saffron is a victim in McNab's eyes, Anderson is the villain, "a man consumed by greed and the need for prestige".

Unlike Abe Saffron, who presumably owned eight sex shops for higher motives.

Named in the South Australian parliament as a key figure in organised crime, Saffron was stopped at Perth airport in 1973. In his diaries, police found the name and addresses of a NSW judge, NSW police officers and a future attorney-general of NSW. Saffron's solicitor at the time was Morgan Ryan, Lionel Murphy's "little mate".

Saffron and Murphy denied meeting but there was no denying Saffron's involvement with deputy police commissioner Bill Allen, whom he met seven times at police HQ. Allen was later jailed for bribing the head of the Special Licensing Police on five occasions.

NCA chairman Donald Stewart called Saffron "a corrupter of police and others".

Shortly before his death, Anderson was interviewed by a University of Technology, Sydney, researcher about those years.

"People got killed for what they might know," he said.

"Money was first raised from gambling, then prostitution and then drugs. I watched it happen. You either went along with it or got out.

"The Cross changed when the police took over the drug scene ... the police became the gangsters.

NSW premier Robert Askin was the godfather and corruption reigned supreme from the dustman to the premier."

Perhaps because of Saffron's litigious nature, McNab did not delve too deeply into his client's darker side.

Instead, he wheeled out evidence of donations to the Benevolent Society and Moriah College and describes Saffron as a model prisoner.

Whatever may emerge after Saffron's death yesterday, aged 87, in Sydney's St Vincent's Private Hospital, we'll probably never know the full extent of the power and influence that this clever draper's son from Annandale wielded for 40 years over police, vice and politicians of all stripes in the city of Sydney.

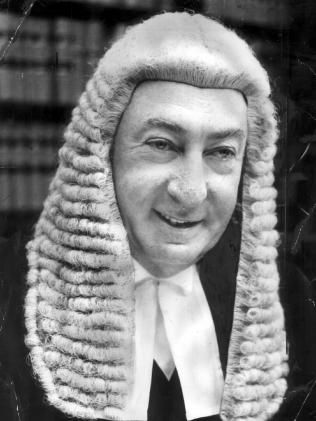

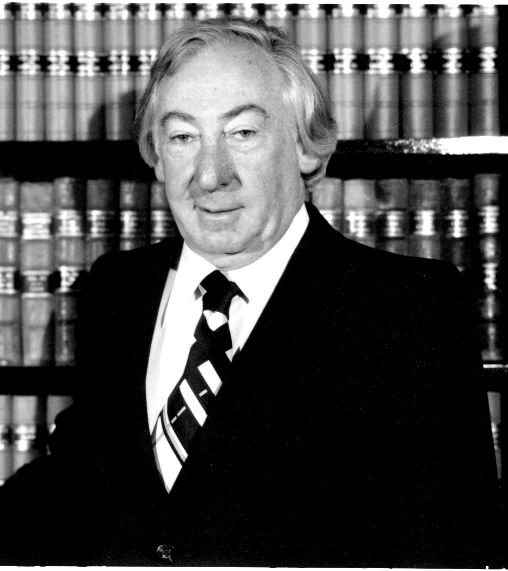

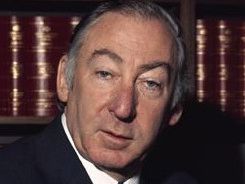

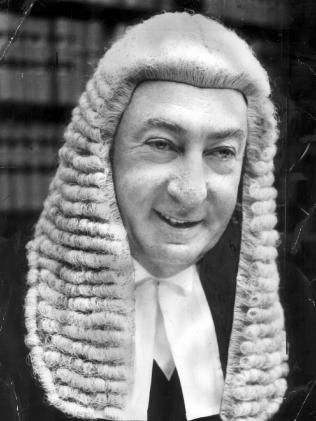

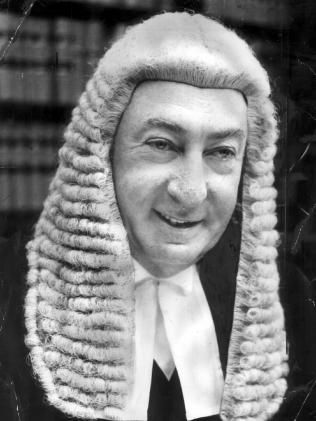

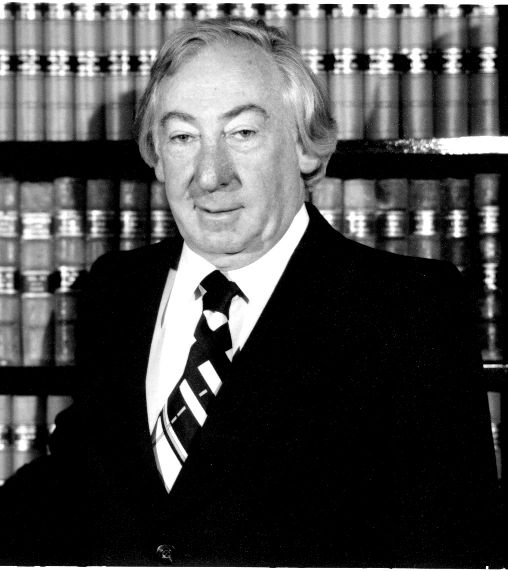

Lionel Keith Murphy- former Justice of the High Court Of Australia

Abe Saffron the notorious crime boss of Kings Cross and Australia's Crime Boss who had control of many senior senior politicians, police, government employees, lawyers, barristers, magistrates, judges, justices, premiers, prime ministers, business people and organisations, bankers, financiers, criminal networks gangs and organisations and major criminals.

One of Abe Saffrons control methods was holding embarrassing tapes and videos of such senior people in embarrassing sexual and other encounters ... and other damaging information,which is made public would instantly destroy their career and likely land them in prison with a serious criminal conviction .... Abe Saffron and his even more powerful senior silent partners knew that this was a tried and proven method to keep control of these people .... before such well connected people were allowed to rise to their powerful positions such as a Justice of the High Court of Australia, a premier of a state,a prime minster, a police commissioners etc ... is was necessary to have serious dirt of their private life ...so there is no way they could not obey orders .... from Abe Saffron and his even more powerful senior silent partners

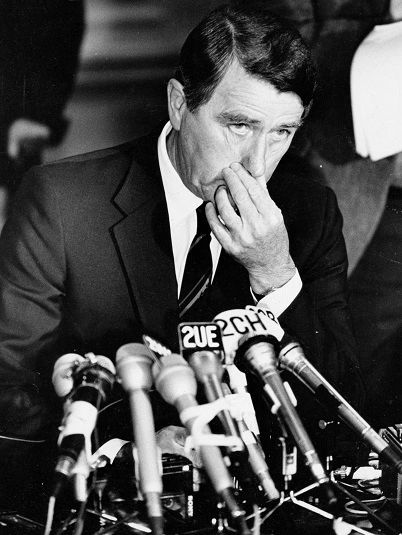

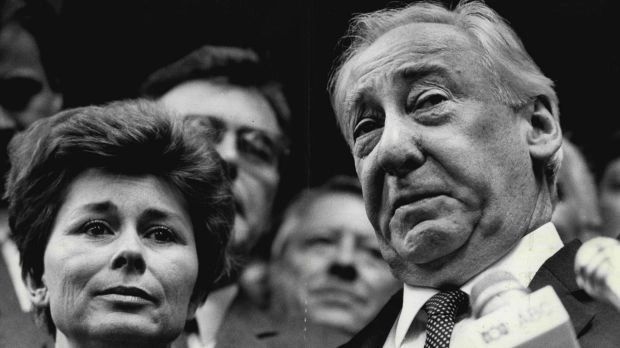

Former high court judge Lionel Murphy. A 1986 parliamentary commission of inquiry investigating Murphy’s conduct identified 15 allegations. Photograph: Lionel Murphy Foundation

Just how close was the former high court judge Lionel Murphy to the notorious crime boss of Kings Cross Abe Saffron?

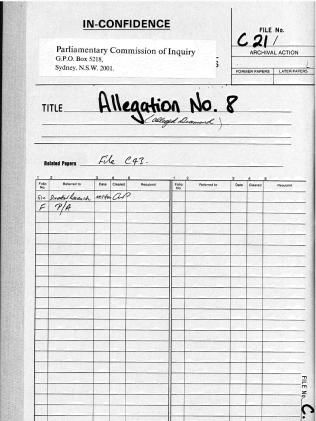

That question preoccupied investigators on the 1986 commission of inquiry into whether Murphy’s conduct constituted misbehaviour in office.

The extent of their concern is revealed in documents released on Thursday, 31 years after the commission was terminated without making findings.

The commission had before it two allegations that Murphy had lobbied New South Wales Labor politicians on behalf of companies associated with Saffron in order to win them lucrative contracts. One was for the refurbishment of Central railway station. The other was for the lease on Luna Park.

The allegations were based on illegally taped conversations between Murphy and his friend, Sydney solicitor Morgan Ryan, which had formed part of the Age Tapes reports in 1984 and later led to the Stewart royal commission.

But was Murphy doing it because of his friendship with Ryan, who was known to be close to Saffron? Or was there a more direct relationship?

In July 1986, investigator Andrew Phelan met with Superintendent Drew at the 20th floor of NSW police headquarters to find out.

According to his file note, Drew reassured him that “apart from what [crime figure] James McCartney Anderson had told Sergeant Warren Molloy, no link between Saffron and his honour had come to light”.

What that particular link was is not disclosed. But Molloy, then special licensing seargent in the Kings Cross region, had extensive knowledge of Saffron’s operations. Molloy was overseas and did not return until a day after the inquiry was wound up, so Phelan never got to interview him.

However, Phelan also noted that “we were told that the vice squad had been conducting a lengthy investigation into allegations that Filipino girls were imported under some racket involving [solicitor] Morgan Ryan to work as prostitutes at the Venus Room”.

“It was suggested that Ernie ‘the good’ Shepherd, head of the vice squad may be able to tell us something about suggestions that Saffron procured females for his honour.”

The police also confided that that they were investigating several allegations that had come out of the Stewart royal commission, “including the alleged involvement of his honour, Ryan, Saffron, the Yuens and police in the Dixon Street casinos matter”.

The file on the commission of inquiry’s investigation into the Luna Park lease reveals that the main evidence they were relying on was from Mr Egge of the NSW police who had given evidence to the Stewart royal commission based on the phone taps he had listened to as part of illegal phone tapping that the NSW police had undertaken. They became known as the Age Tapes.

Ryan had been one of their targets and conversations with Murphy had been picked up.

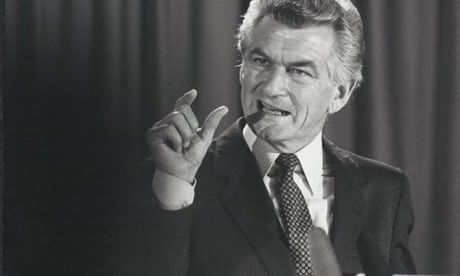

In the early months of 1980, Murphy was alleged to have told his friend that he had intervened with the NSW premier Neville Wran on behalf of the Saffron-linked company to secure him the Luna Park lease.

The government announced in early 1980 that all six tenders were rejected and eventually called fresh tenders. The winner was Harbourside Amusements. In its early incarnation it was controlled by a solicitor, David Baffsky, who was known to act for Abe Saffron, according to the commission files. But later it had Sir Arthur George and Michael Edgley as its public face and Saffron’s nephew as its secretary.

The commission also sought help from the National Crime Commission and the Stewart royal commission into organised crime.

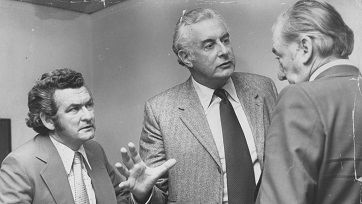

They were sent the transcript of an interview with James West, part owner of Raffles nightclub who claimed that he had met Murphy at Saffron’s place, and that “Murphy was his main man, you probably know that”.

At the time it was wound up, the commission records show it was planning to call Saffron, Ryan, Inspector Molloy and numerous denizens of Sydney’s crime world to give evidence.

Murphy died a few months later. The truth or otherwise of his involvement with Saffron remains unproved.

Abe Safron - The real king of the Cross

Bridget McManus JUNE 17 2010

http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/the-real-king-of-the-cross-20100616-yf8a.html

BEFORE Bob Trimbole and John Ibrahim, before George Freeman and Terry Clark, there was an Australian underworld figure with a story so dirty and so colourful it could span several Underbelly seasons. The original ''Mr Sin'', Abe Saffron, recently featured on an episode of Nine's Australian Families of Crime and an ABC documentary, Mr Sin, screens this week.

Perhaps his relatively recent surfacing in the current stream of true-crime television specials is because even four years after his death, certain people still aren't talking about the man who ruled Kings Cross from the 1950s.

Mr Sin...Abe Saffron.

''Police officers in particular wouldn't talk because they feel the story is still alive,'' says the writer and director of Mr Sin, Hugh Piper. ''I really tried with the NSW police force and I can't help but feel I was fobbed off.''

Drawing on the perspectives of Saffron's son, Alan, former attorney-general Frank Walker and journalists and writers who followed the rumours and royal commissions throughout the decades, the film presents a detailed investigation of the dealings of the notorious gangster, to which nothing more than tax evasion (for which he served 17 months from 1987) ever stuck. Using archival footage and photographs, with minimal re-enactments (one is from a Mike Willesee special in the 1970s, in which Saffron associate Jimmy Anderson plays himself being attacked in a nightclub brawl), the film is ''full of revelations'', Piper says.

''We've put Abe into this social, historical context in a way that hasn't been done before. It's as much an insight into the history of Sydney as it is into Abe and into how the police did their work. Underbellytells us a lot of that stuff but this was before Underbelly. It was about setting up all those models of behaviour that in the long run bore fruit for the people who came after.''

Like many Australians, Piper grew up with the legend of Saffron, the son of Polish migrants who brought nightclubs and strip clubs and then world-class acts such as Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald to Sydney. Melbourne's Truth newspaper ran stories on the scandals of ''Sin City'', which invariably involved Saffron. When Piper moved to Kings Cross in the 1980s, he would catch sight of the ''enigmatic'' Saffron, gold chain glinting through ''a very hairy, broad chest'', and visited his playground, the Venus Room strip joint.

''At two or three in the morning there would be the most extraordinary cross-section of people and naked women walking around,'' Piper says. ''It was a watering hole. The pubs in those days closed at midnight or even earlier and all sorts of people would go to the Venus Room afterwards.''

It was likely the setting of many a deal struck between Saffron and his cohorts, who allegedly ranged from detectives to politicians, union bosses and developers. It was also a hot-spot for wooing women. In the film, Saffron's daughter, from one of his many extra-marital affairs, remembers a devoted father.

His son, Alan, whose book about his father is called Gentle Satan, speaks of the torment suffered by his mother, nightclub dancer Doreen. What isn't included in the film is Alan's claim that Abe had him committed to the infamous Chelmsford psychiatric hospital after convincing police to drop drug charges against his son.

''Alan used to get lots of girls because he was Abe's son and then Abe would turn up at a club with a woman and the doorman would say, 'Your son's down there having a high old time,' and so, in a sense, Alan started cramping his style. Then all of a sudden Alan was busted for drugs and Abe said, 'I'm going to get you sorted out, son.' He was in Chelmsford for a while and he had a lot of electro-convulsive therapy, which I think has had a huge impact on him,'' Piper says. ''There were some incredible stories we couldn't include due to time constraints.''

Bitter though Alan may be at this and the snub he received from Abe's will, he maintains his father was not a violent man but concedes Abe may have ''condoned violence'' by his heavies. The two nastiest crimes linked to Saffron - the murder of anti-development protester Juanita Nielsen and the Luna Park ghost train fire of 1979 - remain unsolved.

''This film isn't glamorising Abe Saffron,'' Piper says. ''It's telling a story that he did create a very glamorous world, particularly in the early years, but by the time he got to the '70s and '80s he'd become more interested in the big end of the town and become a wheeler-dealer rather than trying to create an ambience in the city.

''But still, there are a lot of people with an affection for him and what he represents,'' he says. To put it in a historical context, going back to the Rum Corps, the colony's always been like that and maybe we've always had people like Abe. But I don't want to suggest that Abe is in any way a Ned Kelly figure. Abe was more like an Old Testament emperor: into sex and power.''

Mr Sin: The Abe Saffron Story screens on Thursday at 9.25pm on ABC1 Critic's view, page 38.

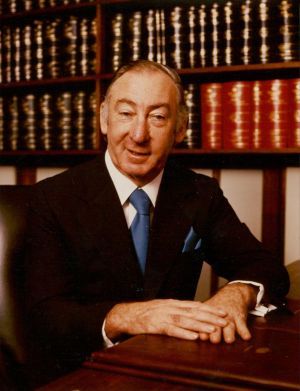

Abraham Gilbert "Abe" Saffron

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abe_Saffron

Abraham Gilbert "Abe" Saffron (6 October 1919 – 15 September 2006) was an Australian nightclub owner and property developer who was reputed to have been one of the major figures in Australian organised crime in the latter half of the 20th century.

For several decades, members of government, the judiciary and the media made repeated allegations that Saffron was involved in a wide range of criminal activities, including illegal alcohol sales, dealing in stolen goods, illegal gambling, prostitution, drug dealing, bribery and extortion. He was charged with a range of offences including "scandalous conduct", possession of an unlicensed firearm and possession of stolen goods, but his only major conviction was for tax evasion.

He gained nationwide notoriety in the media, earning the nicknames "Mr Sin", "a Mr Big of Australian crime" and "the boss of the Cross" (a reference to the Kings Cross red-light district, where he owned numerous businesses).

He was alleged to have been involved in police corruption and bribing politicians. Saffron always vigorously denied such accusations, and was renowned for the extent to which he was willing to sue for libel against his accusers.

Abe Saffron’s Early Life

Saffron was born in Annandale in 1919, of Russian Jewish descent. He was educated at Annandale and Leichhardt primary schools and at the highly prestigious Fort Street High School. Although his mother hoped he would become a doctor, Saffron left school at 15 and began his business career in the family's drapery firm in the late 1930s. He enlisted in the Australian Army on 5 August 1940, and reached the rank of Corporal before being discharged 4 January 1944. Saffron did not serve overseas. Saffron then served in the Merchant Navy from January to June 1944.

Abe Saffron’s Career

Upon leaving the Merchant Navy, he became involved with a notorious Sydney nightclub called The Roosevelt Club, co-owned by "prominent Sydney businessman" Sammy Lee. It is claimed that Saffron began his rise to power in the Sydney underworld through his involvement in the lucrative sale of black-market alcohol at the Roosevelt.

At the time, NSW clubs and pubs were subject to strict licensing laws which limited trading hours and regulated alcohol prices and sale conditions. When Saffron began working at the Roosevelt, alcohol sales were also subject to wartime rationing regulations. A subsequent Royal Commission into the NSW liquor trade heard evidence that in the early 1950s The Rooer being declared a "disorderly house" by the NSW Police Commissioner. After Saffron sold the Roosevelt, it was able to be re-opened. Saffron then relocated to Newcastle; he worked there for a time as a bookmaker, but it has been reported that he was not successful.

When questioned by a Royal Commission about how he had obtained the substantial sum (£3000) with which he bought his first pub licence in Newcastle, he claimed that the money had come from savings he had accumulated from his bookmaking activity, although he was notably vague when pressed about the exact sources of this income.

In 1948 Saffron returned to Sydney and began purchasing licences for a string of Sydney pubs. It was later alleged that he also established covert controlling interests in numerous other pubs through a series of "dummy" owners. The 1954 Maxwell Royal Commission heard evidence that Saffron used these pubs to obtain legitimately purchased alcohol, diverting it to the various nightclubs and other businesses that he operated and selling at black market prices, realising vast profits.

By the 1960s Saffron owned or controlled a string of nightclubs, strip joints and sex shops in Kings Cross, including the Sydney club Les Girls, home of the famous transvestite revue. During this period he began to expand his business operations into "legitimate" enterprises and to establish holdings in other states, such as the Raffles Hotel, Perth, leading several state governments to launch inquiries into his activities.

International connections

The Australian Commonwealth Police alleged that Mr Saffron met with Chicago mobster, Joseph Dan Testa, in 1969, while Testa was in Australia.

Juanita Nielsen Disappearance

One of the most contentious incidents in Saffron's career was his rumoured involvement in the disappearance and presumed murder of newspaper publisher and anti-development campaigner Juanita Nielsen in July 1975. Although no direct connection to the crime was ever established, Saffron was shown to have had proven connections with several people suspected of being involved in Nielsen's disappearance. Saffron owned the Carousel nightclub in Kings Cross, where Nielsen was last seen on the day of her disappearance; his long-serving deputy James McCartney Anderson managed the club; one of the men later convicted of conspiring to kidnap Nielsen was Eddie Trigg, the night manager of the club; it was also reported that Saffron had financial links with developer Frank Theeman, against whose development Nielsen was campaigning.

Expose

In the 1980s investigative journalist David Hickie published his landmark book The Prince and The Premier, which included a substantial section detailing Saffron's alleged involvement in many aspects of organised crime in Sydney. The book's central thesis was that former NSW Premier Robert Askin was corrupt, that Askin and Police Commissioners Norman Allan and Fred Hanson received huge bribes from the illegal gaming industry over many years, and that Askin and other senior public officials had overseen and approved of a major expansion of organised crime in New South Wales.

Using only material that was already in the public domain, obtained from evidence tendered to royal commissions and allegations made by politicians under parliamentary privilege, Hickie devoted an entire section of his book to Saffron's business activities. Among the most damning material was the detailed evidence tendered to the 1954 Maxwell Royal Commission into the NSW liquor trade, which concluded that Saffron had established covert controlling interests in numerous NSW pubs to supply his "sly grog" outlets, and that he had systematically made false statements to the Commission and sworn false oaths before the NSW Licensing Court.

Furthermore, in the second edition of The Politics of Heroin by Alfred W. McCoy, in a chapter summarising the Nugan Hand Bank it is mentioned that Askin and Saffron regularly had dinner together at the Bourbon and Beefsteak Bar and Restaurant, owned by American expatriate Maurice Bernard Houghton.

The NSW Police were unable to effect any substantial convictions against Saffron over a period of almost 40 years, which only served to reinforce the public concerns about his alleged influence over state police and government officials, but after the establishment of the National Crime Authority in the 1980s, he became a major target for the new federal investigative body.

Tax Evasion

In November 1987, following an extensive investigation by the NCA and the Australian Taxation Office, Saffron was found guilty of tax evasion. His conviction was largely made possible by evidence provided by his former associate Jim Anderson, who testified that Saffron's clubs routinely kept two sets of accounts—one set of so-called "black" books, which recorded actual turnover, and another set ("white" books) which were purposely fabricated with the intent of evading tax by falsifying income.

Despite several legal appeals, Saffron served 17 months in jail. Judge Loveday said on sentencing "In my view the maximum penalty of three years is inadequate."

Saffron undertook a number of highly publicised defamation cases against various publications; he unsuccessfully sued The Sydney Morning Herald but was successful in later suits against the authors, publishers and distributors of Tough: 101 Australian Gangsters and the publishers of The Gold Coast Bulletin, which contained a defamatory crossword clue.

Abe Saffron’s Death

Prior to his death he lived in retirement at Potts Point, Sydney.

Abe Saffron died at St. Vincent's Hospital, Sydney in 2006, aged 86.

Abe Saffron was interred next to his wife, Doreen, at Rookwood Cemetery, Sydney.

Prior to Abe Saffron's death he lived in retirement at Potts Point, Sydney.

Abe Saffron’s Legacy

In November 2006 the Sydney Daily Telegraph reported that Saffron's son Alan, would receive only $500,000 from his father's multimillion-dollar estate; the article quoted various estimates of the value of the estate that ranged from A$30 million to as much as $140 million. The article reported that Saffron's eight grandchildren (including Alan Saffron's five children) would receive $1 million each, Saffron's mistress Teresa Tkaczyk would receive a lifetime annuity of $1000 a week and the couple's apartments in Surry Hills, Elizabeth Bay and the Gold Coast and that Melissa Hagenfelds (Saffron's daughter by his former mistress Rita Hagenfelds) would also receive a $1,000 a week annuity and apartments at Centennial Park and Elizabeth Bay. Other reported provisions of the will included bequests of up to $10 million to various charities.[9]

In May 2007 the Sydney Morning Herald published an article on Saffron's reputed involvement in the infamous Ghost Train fire at Luna Park Sydney in 1979, when a suspected arson attack destroyed the popular ride, killing seven people. In an interview with Herald journalist Kate McClymont, Saffron's niece Anne Buckingham linked Saffron to the fire, stating that her uncle "liked to collect things" and that he intended to purchase Luna Park.[10]

At the time of the fire, the park was being leased to property developer Leon Fink (businessman) and his partner, who told the Herald that he had been stopped from purchasing the park by the then state ALP government of Neville Wran—reputedly because Fink's business partner Nathan Spatt had made derogatory comments about Wran's use of a private aircraft belonging to Sir Peter Abeles—and Fink said that Wran once said to him at a function: "While my bum points to the ground, your partner will not get that lease." The Herald story also stated that a parliamentary report revealed that then Deputy Premier Jack Ferguson had told John Ducker(head of the Labor Council of New South Wales) that Wran had decided that Fink would not get Wran's support because he did not donate enough money to the ALP.

In August 2007 Allen & Unwin published the first major biography of Saffron, written by investigative journalist Tony Reeves, author of the 2005 biography of notorious Sydney gangster Lenny McPherson.

In July 2008 Abe Saffron's son Alan returned to Australia from his home in the USA to promote his memoir Gentle Satan: Abe Saffron, My Father and the publication of the book was widely covered in the Australian media. According to a Sydney Morning Herald report, Saffron's book names former Saffron associate James McCartney Anderson as the chief agent of the conspiracy to silence Juanita Nielsen. Anderson (who died in 2003) consistently denied any involvement while he was alive, but police reportedly failed to check Anderson's alibi that he was interstate when Nielsen disappeared.

In an interview with Herald reporter Lisa Carty, Alan Saffron said that he had received death threats over the book because it would name some of the people involved in the Juanita Nielsen conspiracy, but that he was unable to name all those involved for legal reasons, because some were still alive.

Saffron claimed he could name people "much bigger" than former NSW premier Robert Askin and former police commissioner Norman Allan, with whom his father corruptly dealt to protect his gambling, nightclub and prostitution businesses. Saffron specifically referred to:

... one particular businessman I was desperate to name, and there's one particular police officer who is extremely high ranking. They're the biggest names you can imagine in Australia.

According to the Herald article, all the conspirators are named in the original manuscript of the book, which is now in the possession of Saffron's publishers, Penguin, and that the book would be re-published with additional names after people not originally named had died.

A follow-up article published the next day carried Alan Saffron's assertion that his father controlled the vice trade, including illegal gambling and prostitution, in every state except Tasmania and the Northern Territory, and that he bribed "a host of politicians and policemen" to ensure he was protected from prosecution.

Later in his career Abe Saffron reportedly began laundering his huge illegal income through loan sharking and that the late media magnate Kerry Packer was among those who borrowed money from Abe Saffron, allegedly to cover gambling debts.