Princess Diana Murder Cover-Up Turns Deadly

by Jeffrey Steinberg

Nearly

three years after the Paris car crash that claimed the lives of

Princess Diana and Dodi Fayed, the cover-up of that tragedy has taken a

deadly turn, prompting some experts to recall the pileup of corpses that

followed the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Over the

course of four years, after President Kennedy was shot on Nov. 22, 1963,

at least 37 eyewitnesses and other sources of evidence about the crime,

including one member of the infamous Warren Commission, which oversaw

the cover-up, died under mysterious circumstances.

On

May 5, 2000, police in the south of France found a badly burned body

inside the wreckage of a car, deep in the woods near Nantes. The body

was so charred that it took police nearly a month before DNA tests

confirmed that the dead man was Jean-Paul "James" Andanson, a

54-year-old millionaire photographer, who was among the paparazzi

stalking Princess Diana and Dodi Fayed during the week before their

deaths.

From

the day of the fatal crash in the Place de l'Alma tunnel, that killed

Diana, Dodi, and driver Henri Paul, and severely injured bodyguard

Trevor Rees-Jones, Andanson had been at the center of the controversy.

Mohamed

Al-Fayed, the father of Dodi Fayed, and the owner of Harrods Department

Store in London and the Paris Ritz Hotel, has labelled the Aug. 31,

1997 crash a murder, ordered by the British royal family, and most

likely executed through agents and assets of the British secret

intelligence service MI6--with collusion from French officials, whose

cooperation in the cover-up would have been essential.

At

least seven eyewitnesses to the crash said that they saw a white Fiat

Uno and a motorcycle speed out of the tunnel, seconds after the crash.

Forensic tests have confirmed that a white Fiat Uno collided with the

Mercedes carrying Diana and Dodi, and that this collision was a

significant factor in the crash. Several eyewitnesses told police that

they saw a powerful flash of light just seconds before the Mercedes

swerved out of control and crashed into the 13th pillar of the Alma

tunnel. That bright light--either a camera flash or a far more powerful

flash of a laser weapon--was probably fired by the passenger on the back

of the speeding motorcycle. Both the motorcycle and the white Fiat fled

the crash scene, and police claim they have been unable to locate

either vehicle, or identify the drivers or the passengers.

Andanson's White Fiat

Andanson

had been in and around Sardinia during the last week of August 1997, as

Diana and Dodi vacationed in the Mediterranean. He joined several dozen

other paparazzi, who were stalking the couple's every move. He was back

in France on Aug. 30, the day that Diana and Dodi flew to Paris. And

that is where the facts about Andanson's activities and whereabouts get

very fuzzy.

For

reasons that he never revealed, sometime before dawn on Aug. 31, 1997,

less than six hours after the crash in the Alma tunnel, Andanson boarded

a flight at Orly Airport near Paris, bound for Corsica. Andanson

claimed that he was not in Paris earlier in the evening, when the crash

occurred, but he never produced any evidence, save a receipt for the

purchase of gasoline elsewhere in France (which he could have doctored

or obtained from another person), to prove he was not in the city.

His

son James and his daughter Kimberly told police that they thought their

father was grape-harvesting in the Bordeaux region. Andanson's wife

Elizabeth claimed that she had been at home with her husband all night,

at their country home, Le Manoir de la Bergerie, in Cher, until he

abruptly left for Orly, at 3:45 a.m., to catch the crack-of-dawn flight

to Corsica.

Pressed

on her version of the story, Mrs. Anderson later admitted to reporters

and police that her husband was constantly on the run, and she could

have been mistaken about the night in question. She told The Express, a

British newspaper, "It was always very difficult to recall James's

precise movements because he was always coming and going. The family was

very used to that and so never paid a great deal of attention to the

times he came and went."

What

makes Andanson's precise itinerary the night of the fatal crash so

vital is this: He owned and drove a white Fiat Uno. The car was

repainted shortly after the Aug. 31, 1997 Alma tunnel crash, and was

sold by Andanson in October 1997. And, although the official report of

the French authorities investigating the crash concluded that Andanson's

car was not involved in the crash, French forensic reports made

available to The Express told a very different story.

One

report in the files of Judge Hervé Stephan, the chief investigating

magistrate in the Diana-Dodi crash probe, described the tests on

Andanson's Fiat: "The comparative analysis of the infrared spectra

characterizing the vehicle's original paint, reference Bianco 210, and

the trace on the side-view mirror of the Mercedes shows that their

absorption bands are identical." In laymen's terms, the paint scratches

from the Fiat found on the side-view mirror of the Mercedes were

identical to the paint samples taken from the matching spot on

Andanson's Fiat.

The

report continued: "The comparative analysis between the infrared

spectra characterizing the black polymer taken from the vehicle's

fender, and the trace taken from the door of the Mercedes, show that

their absorption bands are identical."

In

short, despite the French investigators' endorsement of Andanson's

alibi, the forensic tests strongly suggested that his car may have been the white Fiat Uno involved in the fatal crash.

John

Macnamara, the Harrods director of security, and a retired senior

Scotland Yard supervisor of investigations, told reporters: "Mr.

Andanson had for some time been a prime suspect who had relentlessly

pursued Diana and Dodi prior to their arrival in Paris. We have always

believed that Andanson was at the scene and that more investigation

should have been done into his possible involvement."

Macnamara

added, "We believe that his death is no coincidence and that this is a

line of inquiry which may help to discover the truth. Was Mr. Andanson

killed because of what he knew? That is a question we want answered."

The `Suicide' Soap Opera

Needless

to say, Andanson's death stirred up renewed interest in Diana's death

at a most inopportune time for the British royals, and those in France

who abetted the cover-up. Sometime in September, an appellate court in

Paris will rule on Al-Fayed's motion to order Judge Stephan to reopen

the crash probe, based on the fact that Stephan shut down his probe

before certain vital avenues of inquiry were fully explored, and in

contradiction to his own interim report, which cited several glaring

paradoxes in the evidence that remained unresolved at the point that he

abruptly closed down his investigation last year and blamed the crash on

driver Henri Paul.

For

example, U.S. intelligence agencies, including the National Security

Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Defense Intelligence

Agency, have all acknowledged, in response to Freedom of Information Act

queries, that they have thousands of pages of documents on Princess

Diana. Those documents, for the most part, remain under lock and key. In

addition to those documents and other relevant evidence, it has been

recently exposed that a secret U.S.-U.K. joint surveillance program,

code-named "Project Echelon," had apparently been involved in

round-the-clock monitoring of Princess Diana's telephone conversations,

while she was at home in England and travelling around the globe.

Until

the contents of these U.S. government files and electronic intercepts

have been reviewed by French investigators, Al-Fayed's lawyers have

argued, the probe cannot be considered complete. And the U.S. Justice

Department continues to stonewall on indicting three Americans who were

involved in an attempted $20 million extortion of Al-Fayed in April

1998, centered around purported "CIA documents" proving that British

intelligence assassinated Diana and Dodi. While the "CIA documents"

seized from one of the plotters have been confirmed to have been clever

forgeries, questions remain about the accuracy of the content of the

documents.

In a flagrant effort to dampen interest in the Andanson factor, the June 11 Mail on Sunday, a pro-royalist tabloid, ran a story proclaiming "Wife's Affair Led to Paparazzi Man's Car Blaze Suicide." The Mail on Sunday dutifully

peddled the French government's cover story: "The millionaire

photographer who trailed Diana, Princess of Wales in St. Tropez just

days before her death, committed suicide when he discovered his wife was

cheating on him, French police have revealed. . . . The eccentric

millionaire--who was hailed by colleagues as one of the godfathers of

paparazzi photography, and who flew a Union Flag over his house to show

his love of Britain--was facing a family crisis at the time of his

death."

Mail on Sunday reporter

Ian Sparks quoted an unnamed colleague of Andanson's at the Sipa Agency

in Paris, making the preposterously contradictory claim that Andanson

"was desperate to save his marriage. We would never have guessed he

would do something so terrible." He committed suicide to save his

marriage! Right.

A

French police spokesman told Sparks, "He took his own life by dousing

himself and the car with petrol and then setting light to it."

Andanson's

widow Elizabeth, and their son James have rejected the idea that

Andanson's death was suicide. Sources close to the family told EIR that

they have pressed French officials to conduct a murder investigation

into Andanson's death 400-miles from his home. The sources dismiss the

bogus "marital problems" story and additionally report that Andanson was

in high spirits over his new job with the Sipa Agency.

The Plot Thickens

Just

after midnight on June 16, just one week after Andanson's death was

first made public, three masked men armed with handguns, broke into the

Sipa office in Paris, shooting a security guard in the foot. The three

assailants dismantled all of the security cameras in the office, and

proceeded to enter several specific offices, clearly aware of exactly

what they were looking for. They made off with several cameras, laptop

computers, and computer hard drives.

Sipa's

office employs more than 200 people, and operates 24-hours a day. The

three invaders spent three hours in the office, holding other employees

hostage. According to one of the hostages, the men were never concerned

about the French police arriving at the scene. This hostage was

convinced that the three "burglars" were themselves working for some

branch of the French Secret Service. Furthermore, the source confirmed

that Andanson had worked for French and, undoubtedly, British security

agencies.

The

owner of Sipa, Sipa Hioglou, has worked closely with French

intelligence, and, not surprisingly, has been one of the primary sources

of the "marital problems/suicide" cover story about Andanson's death,

"confessing" to French police and reporters that Andanson had confided

in him that he planned to take his own life. Hioglou, in the days

following the bizarre break-in and hostage siege of his office, also

told police that he suspected that the raid was done on behalf of a

disgruntled celebrity who was angry that her picture had been taken by a

Sipa paparazzo without her permission.

In

stark contrast, other Sipa employees have told the police that the idea

that Andanson committed suicide was preposterous, and that they suspect

that the break-in was related to his death.

What Is Going On?

The

Sipa raid, the obvious work of French Secret Service assets, raises

some very troubling questions. If Macnamara and Al-Fayed are right, and

Andanson was at the crash site on Aug. 31, 1997, and his white Fiat was

the car that collided with the Mercedes, what documentation exists of

his presence at the tunnel? What photographs exist of the crash scene,

and what do they reveal? Was some of this material seized from the Sipa

offices in the recent break-in, to assure that it never sees the light

of day?

Evidence

has recently come to light, that within hours of the crash, British and

French secret service agencies carried out a series of similar

break-ins at the homes and offices of several photo-agency personnel, in

a desperate search for photos of the crash site that may have been

transmitted in the hours immediately after the Alma tunnel collision,

and before word of Princess Diana's death was made public.

EIR has

obtained copies of sworn statements from two London-based

photographers, Darryn Paul Lyons and Lionel Cherruault, which reveal

that British intelligence was hyperactive in the hours immediately after

the Alma tunnel crash, desperately seeking any revealing photographs

that might have been spirited out of Paris.

Lyons

identified himself as the "Chairman of `Big Pictures,' . . . an

international photographic agency in London, New York, and Sydney,

specializing in obtaining and selling unique and exclusive

celebrity-based photographs." At 12:30 a.m. on Aug. 31, 1997, Lyons

received a phone call from a Paris paparazzo, Lorent Sola, who said that

he had a dozen photographs of the accident at the Alma tunnel. Sola

offered to electronically transmit the photos to Lyons immediately, and

Lyons rushed off to his office, receiving the high-resolution

photographs at approximately 3 a.m. Lyons immediately began negotiating

with several large news organizations in the United States and Britain

to sell the pictures for $250,000.

Lyons

and Sola conferred after word of Diana's death was made public, and

they decided to withdraw the offer of the pictures. Copies of the photos

were placed in Lyons' office safe.

Sometime

between 11 p.m. on Aug. 31 and 12:30 a.m. on Sept. 1, the electricity

at Lyons' office was mysteriously cut, although no other power outages

in the office building or the neighborhood occurred. Lyons, convinced

that either the office was being robbed, or bombed, called the police.

In his sworn statement, Lyons declared that he believed that secret

service agents had broken into his office and either searched the

premises or planted surveillance and listening devices.

Lionel

Cherruault, a London-based photo journalist for Sipa Agency, in his

sworn statement, reported that, at 1:45 a.m. on Aug. 31, 1997, he

received a call at his home from a freelance photographer in Florida,

informing him that he was expecting to soon be in possession of

photographs of the tunnel crash. Cherruault told the Florida contact

that he was interested. After word of Diana's death was announced, the

deal fell through.

But

Cherruault, who was in contact with his boss at Sipa, stated that, at

approximately 3:30 a.m. on Sept. 1, while he and his wife and daughter

were asleep, his home was broken into, his wife's car was stolen, and

his car was moved. Computer disks used for transmitting photographs, and

other electronic equipment, were stolen, and the front door of their

home was left wide open. Even though cash, credit cards, and jewelry

were visible in the study where the burglars stole the computer

equipment, none of those valuables were taken, making it clear that this

was not an ordinary break-in. The next day, a police officer came to

Cherruault's home and confirmed that the break-in was clearly the work

of "Special Branch, MI5, MI6, call it what you like, this was no

ordinary burglary." The officer said that the home had "been targetted."

The man, whose name Cherruault was unable to recall, assured him "not

to worry, your lives were not in danger," according to the sworn

statement.

The official police report of the Cherruault break-in, which has been reviewed by EIR, confirmed

that "The computer equipment stolen contained a huge library of royal

photographs and appears to have been the main target for the

perpetrators."

Another Thread of the Cover-Up

One

of the other still-unresolved issues in the Alma crash probe, three

years after the fact, revolves around the medical evidence. Al-Fayed has

been battling in court in Britain for the right to participate in the

official inquest into the death of Princess Diana, arguing that since

both Diana and Dodi died in the crash, therefore he should be entitled

to officially participate in both inquests. The courts have

preliminarily ruled that he has the right to contest the Royal Coroner's

rejection of his participation in the Diana inquest, which will only

occur after the French appellate process has been completed, sometime

later this year.

However,

in April of this year, the attorneys representing Al-Fayed received a

copy of a suppressed memorandum, prepared by Professors Dominique

Lecomte and Andre Lienhart, two French forensic pathologists working for

Judge Stephan, suggesting that British authorities, including the Royal

Coroner, Dr. Burton, had interceded to conceal some aspects of the

official British autopsy. The two French doctors were in London on June

23, 1998, where they met with British coroners Drs. Burton and Burgess,

forensic pathologist Dr. Chapman, and Scotland Yard Superintendant

Jeffrey Rees. They were given copies of the English autopsy report on

Princess Diana, but, according to their contemporaneous notes on the

meeting, were told that the document was provided for their "private and

personal use," and that it should not be included in the formal file of

Judge Stephan.

Any

material in that official investigative file was automatically made

available to attorneys representing all the interested parties in the

French probe, including Al-Fayed's attorneys.

This

two-and-a-half year suppression of the Lecomte-Lienhart memorandum has

once again raised serious questions about the legitimacy of the

"official" autopsy of the Princess of Wales, including questions that

arose at the time of her death, as to whether she was pregnant.

The

mayhem surrounding the deaths of Diana and Dodi, and now Andanson,

raises questions about the circumstances in Paris on that night in late

August 1997--questions that the House of Windsor in general, and Prince

Philip in particular, have long sought to suppress. The time may be fast

approaching that the well-orchestrated three-year cover-up is about to

blow apart, and at least part of the truth about the death of the

"People's Princess" see the light of day.

And that is something that the Windsors and the mandarins of MI6 may not be able to survive.

New `Diana Wars' in Britain

Put Focus on LaRouche

by Jeffrey Steinberg

On June 4, the London Daily Telegraph, the

flagship publication of the British monarchy and the Club of the Isles'

Hollinger Corp., published a crass slander against Lyndon LaRouche,

headlined "U.S. Cult Is Source of Theories." The article charged that

LaRouche, EIR, and the New Federalist newspaper were all behind a "Diana

conspiracy industry," and that LaRouche, in league with London-based

billionaire Mohamed Al Fayed, was "accusing the Queen of ordering the

assassination of Diana, Princess of Wales."

Apart

from the fact that the article was pure fiction, there were two

significant things about the story--which accompanied a much longer

article that trashed a British Independent Television (ITV) documentary,

entitled "Diana: The Secrets Behind the Crash," which had aired the

previous night, and which had been followed by a live televised debate

on the Princess's death:

First, the Daily Telegraph smear

was authored by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, an avowed British Secret

Intelligence Service (MI6) stringer, who spent from late 1992 through

the spring of 1997 in Washington, D.C. orchestrating a similar slander

campaign against President Bill Clinton. Allowing Evans-Pritchard's

by-line to appear on the "icebox" slander of LaRouche was a blunder of

strategic significance, which underscored the truth behind LaRouche's

charge that all of President Clinton's enemies, including in the upper

echelons of the British oligarchy, are also enemies of LaRouche.

The

blunder also underscored the fact that there is a "battle royal" under

way within the British ruling class, which goes far beyond the issue of

the death of Princess Diana. The battle touches on matters of global

geopolitics, and how the British oligarchy intends to survive the worst,

systemic financial breakdown crisis in modern history.

The

"Torygraph" slander also marked a decisive break in the Club of the

Isles' policy of keeping LaRouche's name out of print in Britain. It has

been long-recognized by the City of London-centered financier

oligarchical grouping headed by the Royal Consort, Prince Philip, that

LaRouche and EIRhave been a powerful factor in exposing their

dirty machinations worldwide, and have also been an important

contributing factor in an eruption of political warfare against the

Windsors, even from among the British elites.

The LaRouche role in the Windsors' troubles came to the surface in 1994, when EIR published "The Coming Fall of the House of Windsor," a Special Report exposing

the role of Prince Philip and his World Wildlife Fund (WWF, now the

World Wide Fund for Nature), in triggering the worst genocide in modern

history in the Great Lakes region of Africa. Even as EIR's

exposés of the Windsors circulated throughout the world diplomatic

community and among factions of the British establishment, with rare

exceptions, the name "LaRouche" was banned from the British

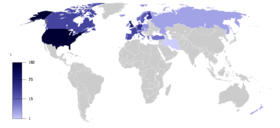

press.[FIGURE 1]

All that changed, beginning with the June 4 Evans-Pritchard diatribe. The article not only accused LaRouche and EIR of

heading the "conspiracy industry," and of accusing "the Queen of being

the world's foremost drug dealer." But also, it linked LaRouche to

Mohamed Al Fayed, Harrods department store owner and the father of the

late Dodi Fayed, in a campaign, Evans-Pritchard wrote, "aimed at

discrediting Tiny Rowland, Mr. Al Fayed's longtime business rival, ...

according to Francesca Pollard, a former operative for the Fayed

security machine." As EIR revealed in its 1993 unauthorized

biography of Rowland, Pollard, whose family was robbed of its fortune by

Rowland, was threatened and then paid off by Rowland, to be a source of

trash against Al Fayed. Following the Aug. 31, 1997 car crash in Paris

that claimed the life of Princess Diana, Dodi Fayed, and their driver,

Henri Paul, Rowland was deployed by the British royal family to lead a

slander and harassment campaign aimed at silencing Mohamed Al Fayed, who

has stated publicly that he is "99.9% certain" that Diana and Dodi were

the victims of a murder plot.

Battle of the Documentaries

The

trigger for the slanders against LaRouche was the airing of the ITV

documentary on the evening of June 3, followed by a live TV debate,

which featured this author. The ITV documentary provided dramatic new

evidence supporting the case that Diana and Dodi were murdered (see "New

Holes in Cover-Up of Diana Murder Plot," EIR, June 12, 1998), and highlighted several investigative leads that were first published in EIR, including the possibility that driver Paul was blinded by an anti-personnel laser.

During

the live TV round-table debate, this author discussed Princess Diana's

decade-long war with the House of Windsor, including the impact of her

November 1995 BBC Panorama interview, in which she charged that her

estranged husband, Prince Charles, was unfit to be King; and, the

reaction of the establishment to her actions, which amounted to a

collective shriek, "Off with her head!" Rowland's personal involvement

in the campaign to cover up the truth about the Paris crash, and to

destroy Mohamed Al Fayed, was also aired, much to the chagrin of the

producer and host of a Channel 4 "Dispatches" documentary on the Diana

death that aired the following night. Channel 4 tried to dismiss as

fantasy every piece of evidence refuting the "drunk driver"

theory.[FIGURE 2]

The Channel 4 "Dispatches" program included a slander of this author and EIR that

was even more explicit on the question of Prince Philip. Although this

author was interviewed on camera for more than two hours by Channel 4

host Martyn Gregory, less than one minute of that interview was shown on

the hour-long "Dispatches" diatribe. And, that brief segment waxed

hysterical about EIR's refusal to "rule out" the possibility that

Prince Philip ordered the murder of Diana and Dodi. Indeed, British

press accounts of the relationship between Prince Philip and Lady Diana,

particularly during the brief period of her relationship with Dodi

Fayed, revealed that the Royal Consort was in a constant blind rage over

Diana's public disdain for the Windsors, and particularly her implicit

challenge to their legitimacy on the British throne.

Gregory was given several pages in the Sunday Telegraph on June 7, to continue denouncing LaRouche, EIR, and

Al Fayed. In an article regurgitating the "Dispatches" disinformation,

Gregory wrote: "The numerous hares Mohamed Fayed has set running in the

colours of sundry conspiracy theories are typified by Geoffrey [sic]

Steinberg, chief reporter of Executive Intelligence Review, a

small-circulation American magazine that specializes in conspiracy

theories. He was yet another guest on the side of the motley crew

supporting ITV's Wednesday night programme.

"This

is the man who told Dispatches he `could not rule out the possibility'

that Prince Philip was involved in the `murder of Diana.' We decided not

to take Steinberg seriously at all."

Defending `Mr. Big'

Not

so for MI5, another British intelligence agency. On June 10, Francis

Wheen, a writer for MI5's favorite leak sheet, the political satire

magazinePrivate Eye, penned another anti-LaRouche diatribe, in the London Guardian. Wheen, who had published smears against LaRouche in 1996, fixated on EIR's

targetting of Prince Philip, whom Wheen affectionately referred to as

"Mr. Big." "Many weird characters enjoyed their 15 minutes of fame

during last week's flurry of TV programmes about Princess Diana," Wheen

began, "but none was weirder than Jeffrey Steinberg, who appeared on

Wednesday night's `studio debate' and again on Channel 4's Dispatches

the next evening. There was, he admitted, `no smoking-gun proof' that

Prince Philip ordered British intelligence to assassinate the Princess;

nevertheless, `I can't rule it out in all honesty.' "

Wheen complained, "So who is he? For some reason, viewers were not informed that the grand-sounding Executive Intelligence Review is in fact the weekly propaganda magazine of Lyndon H. LaRouche." Wheen almost got it right, when he noted, "Executive Intelligence Review has

supported Al Fayed in his vendetta against Tiny Rowland and Lonrho; and

when Michael Howard refused Al Fayed's application for British

citizenship, LaRouche published a defamatory article about the family

connection between Howard and Harold Landy, the former chairman of a

Lonrho subsidiary." Wheen then digressed into the ID-format slander that

was perfected by the mid-1980s dirty tricks slander salon, run by Wall

Street Anglophile spook banker John Train, as part of the "Get LaRouche"

task force of the U.S. Justice Department and private agencies that

framed up and railroaded LaRouche to prison. Wheen recited the litany of

smears: LaRouche says "the Queen runs an international cocaine

smuggling cartel," that "Henry Kissinger is a communist agent," and,

interestingly, that "the Italian banker Roberto Calvi was murdered by

the Duke of Kent." (Calvi was himself a member of the extended royal

family.)

International terrorism

Wheen

then touched on another sore spot of the House of Windsor and Club of

the Isles: the British hand in sponsoring and harboring international

terrorism. He tried to twist EIR's exposé of London's role in

safe-housing dozens of major terrorist organizations, a fact the U.S.

State Department and the CIA have acknowledged in written documents. "In

recent years," Wheen wrote, "LaRouche and Steinberg have been pursuing

another `unique' theory--that `international terrorism' is masterminded

by none other than Lord [William] Rees-Mogg and the Daily Telegraph reporter

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard.... LaRouche claims [that] Rees-Mogg and

Evans-Pritchard are part of a `powerful London-centerd apparatus that

declared war on the United States immediately after the inauguration of

President Clinton.' Whitewater, Troopergate, Paula Jones, Monica

Lewinsky--all these scandals can be traced back to our double-barreled

desperadoes.... But Rees-Mogg and Evans-Pritchard are merely servants of

the `powerful London-centered apparatus.' The Mr. Big whose orders they

obey is Prince Philip.... The intention, according to LaRouche, is to

discredit, and destabilise the U.S. until it is forced to become a

British colony once again, thus taking the House of Windsor another

giant stride on its road to world domination."

Wheen

continued, "Only one person in Britain was powerful enough to thwart

the conspiracy--Princess Diana, who had `declared war' on the royal

family in her Panorama interview. And so she had to be killed."

Wheen

ended on a curious, slightly ominous, note: "This alliance between Al

Fayed and Lyndon LaRouche seems risky, to say the least. Why should a

prominent public figure aid and abet such an unscrupulous

fantasy-merchant? If LaRouche doesn't wish to sully his reputation, he

must disown Al Fayed forthwith," Wheen wrote.

A half-dozen other slanders followed the Guardian article, in the Scotsman, on

BBC-4 Radio, and even in the Danish press. One factor that clearly got

the royals' blood boiling was that, according to the major British TV

rating service, 12.5 million Britons watched the ITV documentary, and

most of them also watched the studio debate that followed the evening

news. On June 4, German national television aired the entire ITV

broadcast, and major German dailies published lengthy excerpts from the

transcript. In contrast, fewer than 3 million British viewers watched

the Channel 4 smear the following evening. And, a Mirror newspaper

poll, published on June 7, suggested that an overwhelming majority of

Britons are convinced that there was more to the death of Diana than a

traffic accident.

The Strategic Battle

As EIR has

said from day one, the death of Princess Diana is the scandal that

could hasten the fall of the House of Windsor. But, the future of the

Club of the Isles oligarchy hangs in the balance today in a number of

ways. The probe in Paris of Diana's death, if it turns up compelling

evidence of a murder, or even of aggravated manslaughter caused by a

paparazzi mob notorious for its links to British intelligence and the

Crown apparatus, would certainly bring down both the Windsors and the

current Socialist government in France, which also is deeply implicated

in the crash and the cover-up.

On

other fronts, the British establishment is torn over how to deal with

the onrush of the financial collapse. Prince Philip and his circle have

no compunctions about throwing the world into decades of chaos and

genocide, in order to retain oligarchical control. But other, less

insane forces within the City of London financial elite are apparently

asking, "What do we get out of such chaos and destruction?" and may be

seeking a new political alliance, perhaps with the United States, and

sane forces on the continent who are opposed to the suicidal Maastricht

Treaty.

Other

issues that are causing divisions among the British elites include

Britain's stance on the European Monetary Union, and the euro single

curency. Furthermore, factions on the continent that share Prince

Philip's impulse to play "chaos warfare," may be pressing for a new

assault on the Asian currencies, including the Japanese yen, through the

major continental banks and their offshore hedge funds, even though

such a move at this moment would almost certainly trigger a global

financial explosion with unpredictable consequences.

Within

the extended European oligarchy, which has, for decades, been under the

boot of Prince Philip's Club of the Isles, there is intensive

in-fighting and factional warfare, adding further to the crisis

atmosphere spreading across Eurasia. The common point of agreement among

the "chaos" factions within the British and continental oligarchies, is

that the power of the United States, as the pillar of the nation-state

system, must be destroyed in the immediate period ahead, lest LaRouche's

ideas for a nation-state-centered New Bretton Woods solution to the

present global mess, be adopted, along with LaRouche's vision for a

Eurasian Land-Bridge plan of global economic reconstructed.

New holes in cover-up of

Diana murder plot

Shortly

after midnight, on Aug. 30-31, 1997, David Laurent, an off-duty senior

French police official, was driving alone in his car on the right bank

of the Seine River, heading toward the Place de l'Alma tunnel where,

moments later, Diana Princess of Wales, her companion Dodi Fayed, and

driver Henri Paul would die in a car crash. As he drove, Laurent was

passed by a speeding white Fiat Uno, according to accounts he provided

nine months ago to French Criminal Brigade police probing the Diana

crash. As he approached the tunnel, Laurent noticed that the Fiat Uno

that had sped by him, was now crawling along in the right traffic lane,

almost at a standstill, just before the tunnel entrance.

Although

the behavior of the Fiat driver was a bit bizarre, Laurent drove on. It

was, after all, Saturday night on the final weekend of the summer, and

there were a lot of strange goings-on on the streets of Paris. Less than

a moment later, however, Laurent heard a loud explosion from inside the

tunnel, as he was driving a short distance ahead.

It

was not until the next morning that Laurent realized that the explosion

he had heard from inside the tunnel was the crash that claimed the

lives of Diana and her companions. And it was not until several weeks

later that police forensic tests confirmed that the crash had been

caused by a collision between the Mercedes 280-S carrying Diana, Fayed,

Paul, and bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones, the sole survivor of the crash,

and a Fiat Uno. Within hours of the crash, police at the scene had

gathered up evidence--a side mirror and fragments of a tail

light--suggesting that a two-car collision had occurred. A police

sketch, drawn at the crash site, labeled a section of the tunnel the

"collision zone." Several witnesses, interviewed during the first week

after the crash, had described a small hatchback car, cutting in front

of the Mercedes at the tunnel entrance, jamming its breaks inside the

tunnel, fleeing the crash scene, and so on.

But,

until Laurent's critical piece of the story became public in early

June, the role of the Fiat had remained ambiguous--despite the fact that

the car and its driver have disappeared. Was the missing Fiat

tragically in the wrong place at the wrong time, or was it critical to

the most spectacular vehicular homicide in history?

Laurent's

description of the Fiat, speeding to a spot near the tunnel entrance,

less than a minute ahead of Diana's car, which was under chase from

several other cars and motorcycles, strongly suggests the latter

possibility.

For

reasons yet unexplained, Laurent's crucial eyewitness account was

withheld from the chief investigating magistrate, Hervé Stephan, for

months.

This

is not the first time that the French police in charge of the

investigation have tampered with evidence. Within hours of the crash,

French police had told reporters that the Mercedes carrying Diana had

been travelling at speeds of more than 120 miles per hour. How did they

know? They told reporters that the speedometer of the mangled Mercedes

had been frozen at more than 120 mph. EIR investigators determined that the French "leak" had to be a lie. Daimler Benz safety experts had told EIR reporters

that, in any crash, the speedometer immediately goes back to zero. Two

weeks later, the French police "corrected" the error; but this time, the

media scarcely reported the correction. Similarly, French police had

lied to reporters that Diana had been pinned in the rear compartment of

the Mercedes, and saying that this was why it took so long to get her

into an ambulance and to a hospital. Photographic evidence and

eyewitness accounts later proved that it, too, was a premeditated lie by

the French police.

In the case of the Laurent testimony, sources tell EIR that

the police have claimed that they have withheld certain vital evidence

from Magistrate Stephan, to avoid the information falling into the hands

of the attorneys for the paparazzi. The police allegedly claimed that

their investigation "would be jeopardized" if the paparazzi were to

learn crucial details.

The Laurent revelation, which was leaked to the London Daily Mirror on

June 4 by a well-placed French police source, was not the only new

piece of evidence to emerge in early June. On June 3, the British

independent television network ITV aired a one-hour investigative

report, "Diana: The Secrets Behind the Crash," that seriously discredits

French police claims that driver Henri Paul was drunk at the time of

the crash.

The

assertion that Paul was drunk and high on two prescription drugs is

pivotal to the ongoing effort, by the French government and the British

establishment, to cast the crash as nothing more than a case of

reckless, drunk driving. The claim that Paul had blood alcohol levels

three times the legal limit at the time of the crash, was based solely

on tests conducted by French coroners within hours of the crash.

Independent forensic experts, including Dr. Peter Vanesis of the

University of Glasgow, who reviewed the autopsy report, had harsh

criticisms of the post mortem on numerous technical grounds.

The ITV report revealed that the forensic tests also showed a near-lethal level of carbon monoxide as well. EIR has

independently learned that it was a separate toxicological test on

Paul's blood sample, that revealed a carbon monoxide level of more than

30% at the time of the crash.

Yet,

Dodi Fayed had no carbon monoxide in his blood. Is it possible that

Paul could have had high levels of alcohol, traces of two prescription

drugs, and toxic levels of carbon monoxide in his blood at the moment of

the crash, and yet Fayed had no carbon monoxide present? Not if the

carbon monoxide was inside the passenger cabin of the Mercedes.

Furthermore,

if Paul had been somehow poisoned with carbon monoxide sometime prior

to getting behind the wheel of the Mercedes, experts interviewed by ITV

say he would have shown obvious signs, such as dizziness, loss of

balance, loss of depth perception, and an unbearable, throbbing pain in

his temple. Security camera video footage of Paul, taken in the lobby of

the Ritz Hotel between 9 p.m. and midnight, and aired in the ITV

documentary, clearly showed that Paul had none of the tell-tale signs of

being drunk or suffering from the effects of carbon monoxide.

In

a live television interview, aired one hour after the ITV broadcast,

the documentary's host, Nicholas Owen, stated that he believed that the

blood sample used in the post mortem was probably not taken from

Paul. There were a dozen other corpses in the Paris city morgue at the

time that Paul was brought in. This startling conclusion by Owen, adds

further weight to EIR's charge that the French police--as

distinct from chief investigating Magistrate Stephan--have been running a

vicious cover-up of the events surrounding the crash.

The

ITV documentary also cited several eyewitness accounts that a powerful

burst of light inside the tunnel, seconds before the crash, may have

blinded Paul. Owen showed a commercially produced anti-personnel laser,

that he purchased in a Paris shop for $300, to buttress the possibility

that such a device was used in the vehicular attack.

EIR Counterintelligence

Director Jeffrey Steinberg appeared along with Owen and a half-dozen

other investigators and expert analysts on the nationally televised

interview show. Details of that broadcast and the vortex of media

controversy, sparked by the ITV show and a second documentary, aired on

June 4 on Channel Four TV in Britain, will appear in a forthcoming EIR (see also, the Editorial in this issue).

In

a move that promises to raise even more questions about what happened

in the Paris tunnel on Aug. 31, 1997, Magistrate Stephan convened an

extraordinary group interrogation, or "confrontation," on June 5, at the

Justice Ministry in Paris. Mohamed Al Fayed, Dodi's father and a civil

party to the case, was invited to participate, as were a dozen

eyewitnesses to the crash. The nine paparazzi who stand to be prosecuted

for manslaughter and interference in the rescue effort, were also

interrogated by Stephan. Details of what took place are not yet

available.

Comprehensive background on the circles implicated in the murder of Princess Diana can be found in EIR's 1997 Special Report,

The True Story Behind the Fall of the House of Windsor.

These articles appear in the June 12, 1998 issue June 19, 1998 issue July 7, 2000 issue of Executive Intelligence Review.

Comprehensive background on the circles implicated in the murder of Princess Diana can be found in EIR's 1997 Special Report,

The True Story Behind the Fall of the House of Windsor

NEW ORLEANS, La. -- An anti-trust lawsuit filed today accuses

NEW ORLEANS, La. -- An anti-trust lawsuit filed today accuses

Bill

Clinton when he was young received a Rhodes Scholarship and later

attended Bilderberg Group meetings, his wife Hilliary Clinton also was

seen attending the 2008 Bilderberg meeting held in Ottowa Canada. Later

on Bill Clinotn became president of the USA twice, and his wife Hillary

Clinton nearky became President of the USA, but ended up in one of th

emlst power positions in USA Politics as Secretary of State and some say

Hillary Clinton is the main representative of the Bilderberg Group in

the USA White House, ans in fact may may more real power in the running

of America than the president Barrack Obama.

Bill

Clinton when he was young received a Rhodes Scholarship and later

attended Bilderberg Group meetings, his wife Hilliary Clinton also was

seen attending the 2008 Bilderberg meeting held in Ottowa Canada. Later

on Bill Clinotn became president of the USA twice, and his wife Hillary

Clinton nearky became President of the USA, but ended up in one of th

emlst power positions in USA Politics as Secretary of State and some say

Hillary Clinton is the main representative of the Bilderberg Group in

the USA White House, ans in fact may may more real power in the running

of America than the president Barrack Obama. The

Rothchild Family...who seem to be healivy involved with the Bilderberg

Group and its sister organisations the Trilateral Commission and the

Council For Foreign Relations

The

Rothchild Family...who seem to be healivy involved with the Bilderberg

Group and its sister organisations the Trilateral Commission and the

Council For Foreign Relations